When I was out poking around in the woods, confirming for local geophile Barbara that indeed her local geologic map wasn’t 100% accurate, I noticed this on the frozen ground:

We have seen this before, in a post back on NOVA Geoblog, almost exactly a year before I took this photo. Here’s another shot from the more recent excursion, taken a foot or so over from the first one:

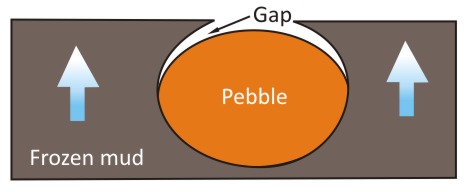

What’s happening here is not that I am showing you particularly high-contrast photos of pebbles and cobbles in the mud. Instead, the reason for the dark line around the sedimentary clasts is that the mud is frozen. When water freezes into ice, it expands in volume by about 9%. This extra volume means that the ice can’t occupy the same space that the liquid water did. So it pooches upwards, as “up” is the direction in which it is least “hemmed in.” Down? No — the expanding ice is not capable of pushing the entire Earth out of its way. North/south? or East/west? Well, there’s already soil there, and it’s pushing back, so there’s no expanding out in those (horizontal) directions. So, “up” it is. That’s all we’re left with: “up” is σ3.

If I were to draw this as a cartoon, here’s the “before” picture:

As the sheet of frozen mud expands upwards, it detaches from the non-expanding (in fact, shrinking, but not by anywhere near 9%) cobbles and pebbles. As the mud ice lifts up higher and higher, the gap between it and the clasts gets more and more pronounced.

Shadows in those gaps make them appear dark to the camera lens.

Ice pulls all kinds of neat tricks like this in the winter. What’s a cool ice phenomenon you’ve observed lately?

Hi, Callan– Yet another interesting observation! However, I would advocate for fine-tuning this one slightly. The impression left from your graphic is that all of the surrounding mud is frozen and expanding upward, leaving the pebble behind, whereas I would argue that only the uppermost few mm of the mud is frozen where it’s in contact with the frigid air. The upper few mm expand upward, but the deeper (slightly warmer) mud, surrounding and beneath the pebble is unfrozen. Otherwise why wouldn’t the pebble be lifted along with the mud? The implication is that larger clasts would tend to sink into the ground over repeated freeze/thaw cycles, which would belie the observation of countless generations of northern farmers that stones/boulders **rise** in their fields every year (similar to the “Brazil nut effect”) thanks to frost-heaving.

Cheers

We had beautiful examples of this a couple weeks ago with a slight twist. In many places there was a thin layer of soil trapped on top of long bladed ice crystals (long = 1″ to 3″). In this case, it seemed to me that the pebbles were left at the ground original surface (or not lifted up as high) because they were heavy. In other areas there were just some nice little forests of ice crystals (Haareis?). My Israeli field partner thought the whole thing very interesting.

Sorry, needle ice.

Thanks for the thoughts, everyone.

Howard: I think the pebbles may well be lifted too, just that they aren’t lifted as much. Not sure as to the total thickness of the frozen layer; I’m guessing it’s more on the order of cm than mm.

Marcie: Check out this video. It sounds like the same thing you’re describing.

CB