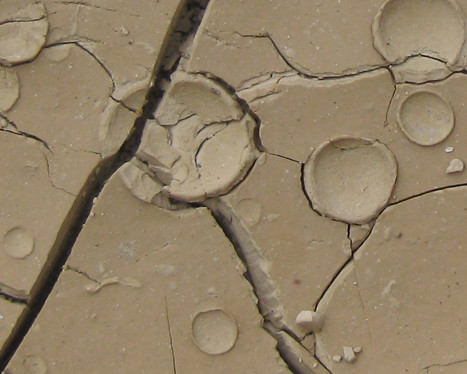

Last Wednesday, I took a field trip to the North Anatolian Fault in Turkey, but I got distracted by this fine looking display of sedimentary structures in a dried-up mud puddle in an old quarry.

The coin, a Turkish lira, is about the same size as a U.S. quarter. What you’re seeing here are dessication cracks (“mud cracks”), and accompanying them are exquisite little raindrop impressions, the minute craters excavated by a light sprinkle of rain after the mud has already started to dry out and “gel.” (If the water which deposited the mud were still there when the rain fell, the standing water would have dissipated the energy of the drops’ impacts, and no craters would have been excavated.)

Here’s a slightly more oblique perspective, to give a sense of how the individual mud flakes are internally laminated, and curl along the edges, producing a concave-up shape.

Note too that the cracks bisect some of the rain drop impressions, and therefore the raindrops fell first, and then the dessication cracks propagated on through them, a nice example of cross-cutting relationships. In some cases, the propagating crack used the “crater rim” of the drops as a mechanical zone of weakness, fracturing there preferentially. Here, let’s zoom in on a couple of nice examples (one from photo #1, a second from photo #2):

If anyone wants a full-sized copy of any of these images for teaching purposes, let me know via e-mail, and I’ll send you one.

Amazing how you make mud, cracks and rain-splatter look fascinating and interesting. The circumstances that made the raindrops left marks had to be indeed unique, but I wonder, what “kind” of rain it must have been. Only a few heavy big drops leaving these deep impressions and the small drops aren’ t many either. The rain couldn’t have been kind of torrential nor dribbling.( I hope this isn’t a silly comment, I just wondered). Thanks a lot for all the educating photographs. Have a save journey home.

No need to apologize — you’re exactly right! This would have been a light spatter of rain — often interpreted as “virga” — those showers that fall from clouds looking like jellyfish tentacles, but most of it evaporates before it hits the ground. Only a few drops make it, and their presence is only preserved in a few rare places, with the right size sediment (mud) in the right state (not too wet, not too dry).