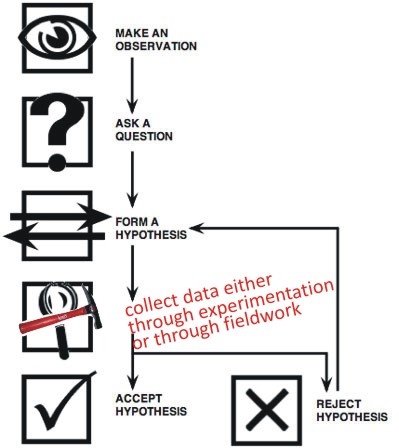

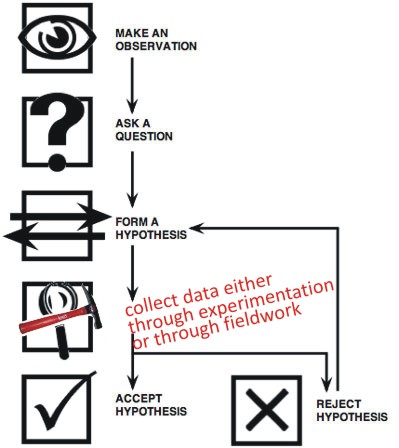

I propose that we replace this:

image source

With this:

Though some experimentation is an important part of the geological sciences, the historical geological record is written in nature. Experiments are any exercises we do where we control the variables and we watch how a system responds to our tweaks (e.g., rock deformation experiments, metamorphic reaction experiments under elevated P/T conditions, sedimentation rates in controlled chambers).

Experiments inform our understanding of nature, but nature comes first. Parts of our understanding may be decoded in a lab setting (e.g., isotopic dating, strain ellipse analysis, or groundwater chemistry), but the data are collected outside and must then be processed indoors. In geology, the big experiment has been run: its result is the planet we see before us. As archaeologists, cosmologists, and crime scene investigators must do, geologists use subtle clues to interpret the past.

Historical sciences have a different fundamental logic than experimental sciences, but they cannot be considered lesser merely because we cannot run experiments on the size and scale of the planet Earth’s 4.5 billion year history. Fixed laws are one thing, a sequence of events with contingency is another. Paul Hoffman has argued that a scientific approach to unraveling past events is geology’s greatest contribution to human thought.

Now that we have (maybe) entered the Anthropocene, we can run experiments of sufficient magnitude to be justly considered “experimentation on the Earth system,” where perturbations of planetary scale have been induced by agriculture, industrialization, and a human population rapidly approaching 7 billion. These are, empirically speaking, experiments on nature “her”self, experiments on the planet Earth. However, these experiments are hardly ideal, as (a) the variables are insufficiently controlled, (b) there is no control planet for comparison, and (c) we live in the “test tube” which hosts the experiment. This means that if the experiment produces civilization-destabilizing results, we have screwed ourselves over big time.

Human civilization is an independent variable in the Earth experiment, in that it has demonstrably altered the natural Earth system with novel conditions of quantifiable extent. Geoscientists may then watch to see how the Earth system responds (the “dependent variables”). What happens to the Earth system when we double CO2 in the atmosphere? NO2? CH4? What happens when we deplete the stratospheric O3 layer? Denude the soil? Chop down a third of all forests? Lower the oceanic pH by 0.7 units?

Image from New Scientist

These are all interesting questions, and I’m sure interested in the answers. I fact, I’d go so far as to say that it’s the most interesting set of experiments that humans have ever run, insofar as their unprecedented scale is concerned…

…But I also have a wee bit of trepidation living in the “test tube” which until now has been so homey and comfortable, …so homeostatic…

Anyhow, what’s my point? Historical and experimental sciences… we need both. As for the Big Experiment, I find it both fascinating and sketchy.

I’m not about to claim that the planet is in danger of being imminently rendered unfit for science, but maybe in addition to experimental science and physical science, we could also use a sense of empathy for the residents of our planet’s coastal plains, for the aragonitic-shell secreting organisms of the world ocean, and for the altitude-limited organisms who have reached the top of their local hill and can climb no further. Do these empathetic considerations deserve higher weight than the knowledge we stand to gain by letting the experiment run?

How do we balance this fascination with finally getting to run an (albeit imperfect) experiment with the fact we must live among the results?

First, an experiment, in a scientific sense, is an intentional test of a hypothesis, not simply messing around to “see what happens.” So I always cringe a little when I see anthropogenic global change described as an “experiment.”

Second, any iconic representation of “the scientific method” is necessarily going to be oversimplified and misrepresentative- appropriate, perhaps, for elementary and middle-school-level discussion, but by high school, it should be replaced by more nuanced understanding. Just as an example, can you describe any experiments Einstein performed? He was primarily a synthesizer. Likewise with Darwin. But no one would argue they weren’t scientists, even though they’re most renowned for a type of work that doesn’t show up in either diagram- in fact, they consistently come up as two of the most known, respected, and important scientists ever.

The point is, we need to get away from a simplistic, iconic representation of the work science does, and honestly describe it as a variety of scientific methodologies, rather than some single “scientific method.”

Good points, including the bit about intention being an essential part of the definition of ‘experiment.’ Sorry to have made you cringe.

“Historical sciences have a different fundamental logic than experimental sciences”

No, a fundamental logic and reasoning, based on observation, independent verificaton of those observations is common to all scientific inquiry, whether experimental, “historical,” descriptive, epidemiological, etc.

The logic and reasoning that leads one to conclude the effects of a treatment in a controlled experiment is not a different kind of logic than a scientist would use, for example, to determine the relative age of rocks according to cross-cutting relationships.

I guess it depends on what you/I mean by “fundamental” — perhaps I should have specified what I meant by the term. They’re both science — but I guess what I meant is that one at its heart is interpretive, while the other is basically manipulative. (no pejorative overtones on “manipulative,” by the way)

Callan,

I always frame the discussion around observations and explanations for the observations. Explanations result in necessary consequences, the search for which produces new observations that must be explained.

Rinse, lather, repeat.

Speculations, hypotheses and theories are then just increasingly improved explanations, and experiments are simply _one way_ to generate new observations.

If you don’t like the experiment you should move to defund it.

As a field soil scientist, I approve of your proposed change to the flow chart at the top. Its a no brainer.

The iteration arrow should maybe branch and also point back to “ask a different question” and “make another observation.” I think maybe geologists are more likely than other scientists to admit that they have no idea what is going on, but forge ahead anyway. Keep collecting well-documented observations in a pile, and maybe some understanding will ooze out from the bottom, like saltpeter.

Another reason the arrow should point back at observation is that you can’t always “see” things before you have some understanding of them. A blacksmith can “see” a horseshoe in the metal he is working on. Everybody else just sees a lump of iron. A geologist can “see” an anticline, everybody else just sees a pile of rocks.