After my cousin Brad caught up with us after our Pinkham Notch roadcut excursion, we started up the trail at Tuckerman Ravine, and then detoured to go via the Lion Head.

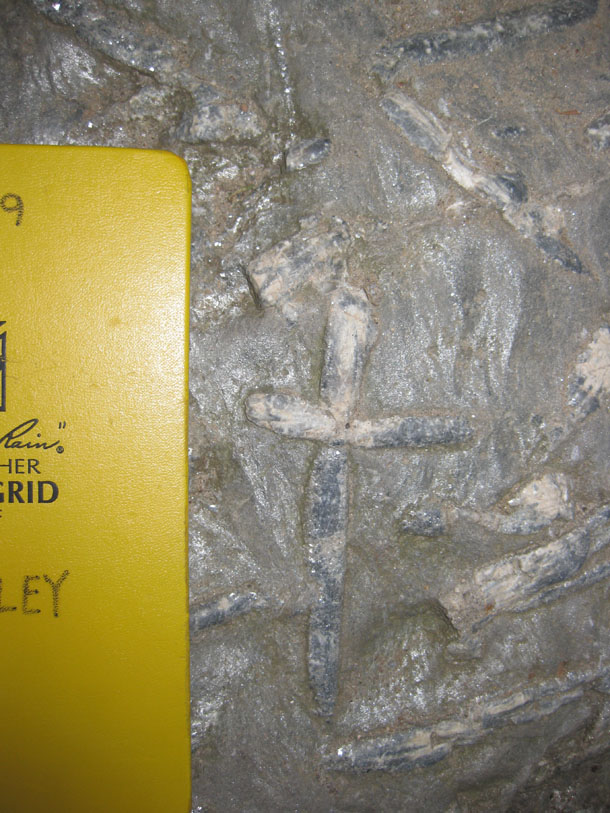

Immediately, we began to see some freaking awesome metamorphic porphyroblasts.

During the Acadian Orogeny (in the late Devonian), the original muds and sands (deep sea turbidite deposits) of the Littleton Formation were metamorphosed. Pale-pink andalusite formed (that’s where these distinctive shapes come from) and then that metamorphosed into white, fibrous sillimanite and eventually retrograded to sericite (muscovite), which I take to be the identity of the gray portion of these partial pseudomorphs. (Petrologists, does that sound right?)

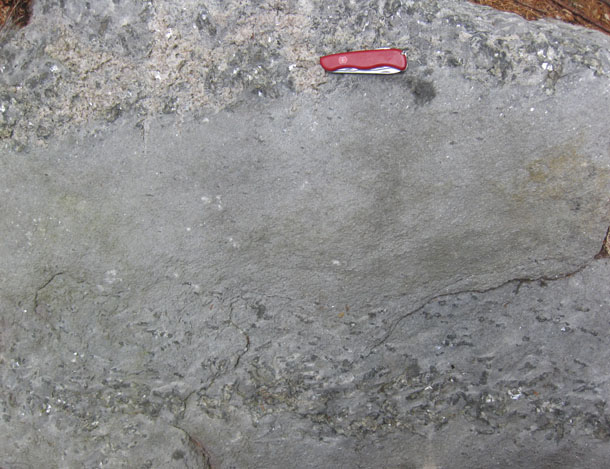

Here’s a formerly sandy layer (top; above the knife) which has been fused to quartzite, and a formerly-muddy layer (most of the outcrop; below the knife) that has been metamorphosed to schist bearing these distinctive pseudomorphs of andalusite:

Same deal here, at the Cragway Springs pull-off mentioned last Friday:

Mud above, sand below — the mud had the right cocktail of elements to provide for the growth of the large metamorphic crystals; the sand had nothing but quartz.

Next up, some metamorphosed graded beds, as noted over the summer. The photos that follow show outcrops and float as seen from the trail, where a tree recently peeled over and exposed them:

Same beds, from a different perspective, with “paleo-up” being photo-“down”…

Here’s another metamorphosed graded bed, seen in a boulder on top of the mountain – again, paleo-up is “down” on the basis of the crisp transition from porphyroblast-rich former-mud and porphyroblast-poor former-sand:

Zoomed in a bit:

Down in Tuckerman Ravine itself, we espied a few more metamorphosed graded beds:

Exposure is not as good here, but here’s what looks to me like right-side-up metamorphosed graded beds:

Two more on the summit boulder pile: paleo-up is to the right here…

…and here:

Same thing here, I think — paleo-up to the right:

This one shows the opposite — paleo-up is to the left. Nice gradation in that direction, whereas there is a nice crisp contact (however deformed) at the right:

Zooming in on a few more porphyroblasts for a last, lingering, loving look:

More later from elsewhere on the mountain…

On the andalusites – the grey parts that stand out on surfaces are probably still andalusite; the white areas are probably a mixture of muscovite and fibrous sillimanite. (The fibrous form of sillimanite tends to nucleate on sheet silicates – it doesn’t grow from andalusite very easily.)

Awesome; thanks!

I climbed Mt. washington when I was in high school. It was in one of those famed white out blizzards. We saw no rocks or view from the top for that matter. Thanks for the tour.

Wow, this is very cool. So, if the mud layers turn to schist and the sand to quartzite, are there any beds with a mixture, or something different? If so, this could be an interesting way to identify some turbidite beds that are poorly sorted mixtures of mud and sand.

Oh yeah, there are many layers that were nowhere near as distinctive as the photogenic examples that I’ve displayed here.

perhaps someday you can show me in person 🙂