![]() The Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia records the switch in late Ordovician time from passive margin sedimentation associated with the Sauk and Tippecanoe epeiric seas, to active margin sedimentation associated with the onset of the Taconian Orogeny to the east. Higher up in the stack, a similar pattern is seen: a return to passive margin sedimentation with the deposition of the Helderberg Group of limestones, and then more active margin sedimentation as the Acadian Orogeny sloughs off huge quantities of siliciclastic sediment.

The Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia records the switch in late Ordovician time from passive margin sedimentation associated with the Sauk and Tippecanoe epeiric seas, to active margin sedimentation associated with the onset of the Taconian Orogeny to the east. Higher up in the stack, a similar pattern is seen: a return to passive margin sedimentation with the deposition of the Helderberg Group of limestones, and then more active margin sedimentation as the Acadian Orogeny sloughs off huge quantities of siliciclastic sediment.

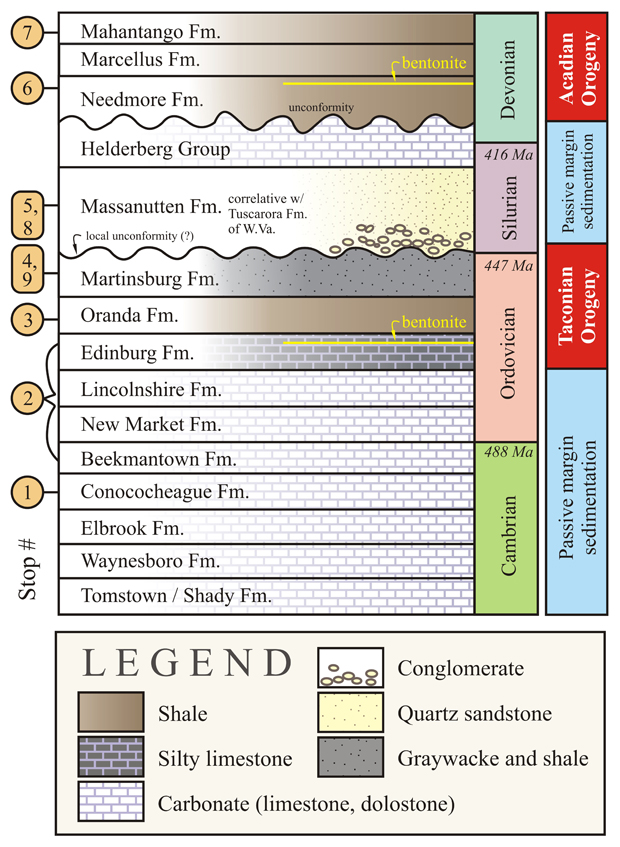

Here’s a cartoon version of the stratigraphic column for the Shenandoah Valley and the strata exposed in Massanutten Mountain in its middle (the whole package is folded into the Massanutten Synclinorium):

Notice how there are two yellow layers in there. These are distinctive packages of bentonite, weathered (devitrified) volcanic ash. Some of these bentonites make for superb regional “time-stamps” that aid in the correlation of strata at widely-dispersed locations. The Tioga Bentonite is an example of this — it’s found throughout the Appalachian Basin and was deposited when an Acadian volcano erupted in massive style. Deeper in the stack is the bentonite I would like to focus on today — the one found in the Edinburg Formation. Known as the Millbrig Bed in North America, this thick layer of (formerly) volcanic ash outcrops as a distinctive yellowish-brown layer that weathers away much faster than the silty limestone above and below it. Here’s a shot of the thickest bentonite (what I guess to be the Millbrig Bed) on the classic “Tumbling Run” outcrop south of Strasburg, Virginia:

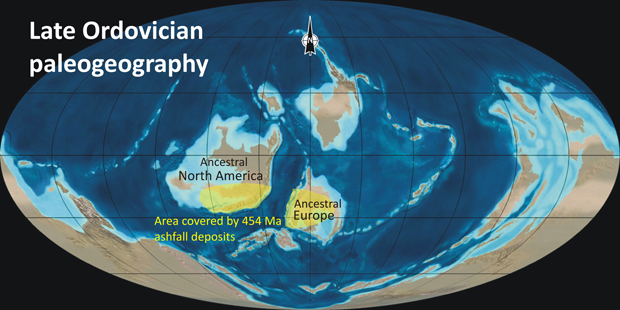

The interesting thing about the Millbrig Bed is that it has been correlated with another bentonite layer, on another continent. The Kinnekulle bed, also known as the “Big Bentonite,” is a distinctive stratigraphic marker in Scandinavia. Because they were erupted at about the same time (~454 Ma), stratigraphers have correlated the two, saying they are the same ash bed, deposited from a truly enormous volcanic eruption – presumably from a volcano somewhere out in the Iapetus Ocean.

(source: Ron Blakey, Northern Arizona University, then modified by me)

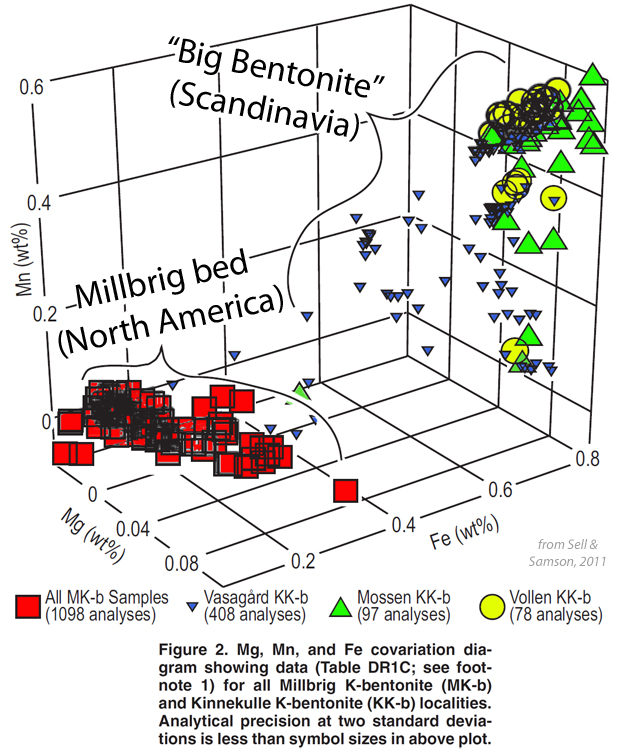

A new paper in Geology by Bryan Sell and Scott Samson of Syracuse University examines whether the European and North American bentonites really match up, however. They find that, on a geochemical basis, they are unlikely to be from the same eruption.

Sell and Samson examined trace elements in crystals of apatite which grew as phenocrysts in the source magma, and were entrained in the ash cloud as it erupted. The trace elements in these crystals can vary widely from eruption to eruption, and so they serve as a good geochemical “fingerprint” that allows us to source the eruption to a specific volcano. They sampled the Millbrig bed in southern Virginia (near the town of Hagan), and used “Big Bentonite” samples from the island of Bornholm, Denmark.

Here’s the key figure in their new paper, (modified and colored by me):

“MK-b” is the North American bentonite; KK-b is the Kinnekulle bentonite of Scandinavia. The key thing to note is the two distinct clusters of data: One in red shows analyses from the Millbrig bed; the yellow, blue, and green show analyses from the “Big Bentonite” in Scandinavia. Based on iron, magnesium, and manganese concentrations, these are two different geochemical fingerprints. Though Scandinavia and Virginia both swallowed a lot of volcanic ash in the late Ordovician, the authors conclude that:

The differences between the MK-b and KK-b in apatite trace element concentrations are so great that they cannot be considered the same bed. This is also true of the intrabed samples; there are no subsections in the MK-b that are similar to any of the vertical subsections in the KK-b. Thus we conclude that no portions of the two beds correlate.

And there you have it. The Big Bentonite isn’t so big after all. It’s two bentonites from two eruptions.

It will be interesting to see how this affects tectonic reconstructions of the position of North America and Baltica during the late Ordovician.

_________________________________________________________________________

Sell, B., & Samson, S. (2011). Apatite phenocryst compositions demonstrate a miscorrelation between the Millbrig and Kinnekulle K-bentonites of North America and Scandinavia Geology, 39 (4), 303-306 DOI: 10.1130/G31425.1

Callan,

The bed you are examining at the Tumbling Run outcrop lies immediately below a thick shale that separates the Lincolnshire Formation from the Edinburg Formation. Is there a mistake with the position of the bentonite in your first figure or am I not recalling the outcrop correctly?

Jay

Hi Jay,

I’m not 100% sure that this is it – but that was my deduction based on wandering around there with the Diecchio & Fichter field guide. If I’ve misplaced it, please let me know! 🙂

I defer to your stratigraphic authority; it would be great to go out there sometime together to hear your take on it.

Callan

Jay,

I just got a moment to check my facts, and according to Fichter & Diecchio (1986), the bentonite layer shown is at the base of the Edinburg Formation. The thick layer immediately above my bentonite is a limestone, not a shale.

So, at least according to their Figure 5, I think I’m correct to place this particular bentonite in the Edinburg, but I should locate the yellow “bentonite” line in my stratigraphic cartoon to a lower position in its host Edinburg “layer.” Would you say that’s the state of things?

Thanks!

C

Callan,

Yes, the cartoon needs to have the bentonite layer moved to the base of the Edinburg. I remember a thick indurated (perhaps cherty) shale separating the Lincolnshire from the Edinburg, but I will have to go back now and look again.

Jay

Hi All,

That bed in the photo at Tumbling is not the Millbrig K-bentonite. It’s actually quite a bit older. This same bed was incorrectly figured in Kolata et al. (1996) as the Millbrig. The Millbrig K-bentonite is actually in the bottom portion of the Martinsburg near the contact with the Oranda. You can find this contact across the road from the photo, over the stream, and through the woods. You can also find the Millbrig just a few miles away in Strasburg.

Take care,

Bryan

Bryan,

Thanks — that’s a key piece of information. Any chance I can sweet-talk you into pinpointing the location of the Millbrig exposure that you know on a Google map and e-mailing it to me at cbentley@nvcc.edu? I run field trips out there on a semi-regular basis, and it would be cool to get all my bentonites straight.

C

The Millbrig(Mud Cave) is intimately associated with other bentonites in my area. It would be interesting to see if the chemistry of the Kennekulle bed correlates to some of those other ash falls found in the Ordovician rocks of the east coast, e.g; the Pencil Cave.

Re: that strat column: I’ve been out of Valley and Ridge geology for awhile now, but since when did the Lower Ord. (and in part Whiterock) Beekmantown become strictly a Cambrian unit? And the New Market (apparently) Lower Ordovician? the New Market is part of the Middle Ord. onlap sequence (see J. F. Read, 1980).

forgot the link, to Read, 1980: http://sepmstrata.org/PDF-Files/Appalachians/CarbTransBasinEvolMidOrdVAAppalRead80.pdf

Thanks Mike. Maybe I shouldn’t have used that image; it seems to be causing problems. It’s a cartoon version of the Shenandoah/Massanutten sequence that I use on a one-day field trip out there; it simplifies a complex story for beginning audiences, but I guess it’s too cartoonized for the erudite stratigraphic audience that this blog attracts. I appreciate your feedback — I’ll strive to come up with a better version — both for this blog and for that field trip…

Callan – I can see why you use it for your class purposes, as it’s a snazzy graphic, and there’s probably not another one like it. You can tell I was into nit-pickin’ stratigraphy, because my inner Fred Read voice was focusing me that way like a laser beam (assume Aussie accent – “Hey, Mike, that’s just not right, I reckon; yeah, right.”). No worries, mate.

Hey Callan! Interesting post. I am working (or better said will be working) on bentonites as part of my PhD and yours caught me attention. I sent you en email with some question. Good posts! 🙂

Just for the record, Kraft (1962) in his GSA Professional Paper on the Ostracoda notes several bentonite layers distinct from and below the one pictured that are situated in the Edinburg on or very near the Lincolnshire/ Edinburg contact at Tumbling Run. Kraft also correlates his stratigraphy with that of Cooper and Cooper (1946(?)) relating to the same section, so if you are more familiar with the Coopers’ section, you can relate the two. Kraft’s Ostracode biostratigraphy seems to be off in places along the Tumbling Run section; I have sampled and etched the limestones for silicified ‘cods and trilobites, inter alia, and find some of his species ranges suspect.

Nice looking strat column. What software did you draw it with? Adobe Illustrator?

Thanks! I used CorelDraw.