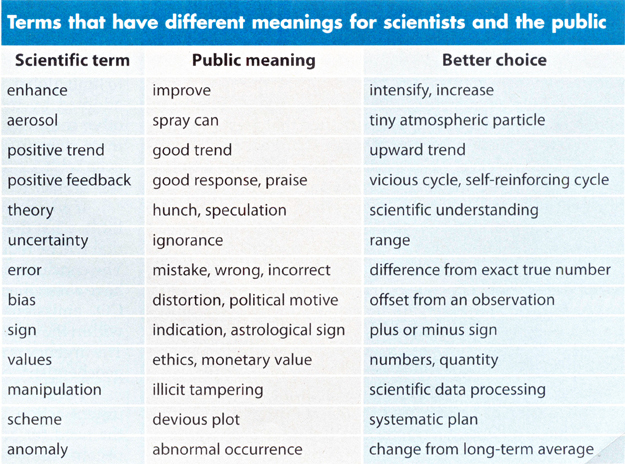

A table from the article “Communicating the Science of Climate Change,” by Richard C. J. Somerville and Susan Joy Hassol, from the October 2011 issue of Physics Today, page 48:

There’s a lot to ponder in this table. It strikes me as an important document – a compilation of one of humanity’s most tragic miscommunications.

You can click on it to make it bigger – large enough that you could embed it in a PowerPoint slide to discuss with your students or peers, if you so opted.

Couldn’t agree with this more.

Yes, that is a good table to keep around. I haven’t read their article yet, but what I’d like to see in communications designed for public consumption is some effort to use the technical terms and also define them. While I think “translating” is certainly useful and important, some (perhaps not all) of such communication can also be used to educate. We always talk about the importance of an educated public in society, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to want the public to be familiar with terms like “anomalous”, for example. So, let’s do both — let’s translate and educate.

oops … didn’t mean that to be a specific reply to Roy-Z, just a general reply to the post, FYI

The role of communications is to inform, not educate. Words that mean one thing to the communicator, and something different (or nothing at all) to the intended audience are called jargon. The above list is scientific jargon (only when used to communicate with the general public), and the golden rule of communications is to never use jargon when writing for a general audience. Trying to ‘educate’ people to understand certain words mean something different when in a scientific context, is basically trying to teach them a different language. You’re asking the audience to do the work (learn your language) because you don’t want to do the work (translate your message into their language).

I disagree. Why so binary? Why can’t communications mostly inform and also have a few nuggets of education? Besides, I’m not sure we could completely untangle ‘inform’ and ‘educate’ anyway.

If you go read the article from which the table is being quoted, you will see that your interpretation of what’s being said is exactly backwards. The point of the table is to suggest alternate words for scientists to use in place of their preferred terms, because the general public has different connotations or definitions for those terms. i.e. the authors of the article and table agree with you.

PamK, who is the “you” in your comment? Brian? Emma? Me?

Callan – I think PamK’s “you” is Emma. I agree, and want to thank you so much for publishing this; the “uncertainty” of the English language frustrates me! I also agree with Emma; I work with very smart people who try and use communication session to educate and just end up just sounding snarky. Their scheme is to throw out a word that has been biased by misuse then wait for conversation so they can point out the error of the listener… Unfortunately ending in positive feedback, and very little communication!

Because often its not Scientists presenting their information to the public, it’s people taking what scientists are saying in a scientific context and applying the ‘general public’ meanings of the words to what they say.

Gee, what about “validate” or “sustainable”? Does anybody, scientist, engineer, or the general public, know what they mean?

Steve, sustainable has got to be one of the most misused words out there. Like many buzz words that die from over-mis-use, the meaning has gone unrecognized and unlearned.

I wrote briefly about the principles of sustainability vs the values of environmentalism – http://turfhugger.blogspot.com/2011/09/adjusting-to-times.html?utm_source=BP_recent

“Viable” and “sustainable” are words beyond the scope of this discussion. They are political jargon, not scientific jargon, hence there is no hope of normalizing them across the general or the educated public!

It would be awesome to cover those terms (and others) in an intro course – it took a couple occurrences for me to understand what was meant by “anomaly” when it was used without explanation in one of my classes.

This must get easier with time, but my first interpretation of these terms is still the generic – when someone says aerosols, I immediately think of AquaNet, frankly. It would be great to introduce these concepts in K-12, to start that public education sooner.

Another common word that has different meanings is “significant”, when used to refer to the statistical significance of results. Yes, the results are significant statistically, but the difference may be too small for the general public to notice.

I haven’t got access to Physics Today at the moment, but would LOVE to know whether that chart is based in research or not. Could you let us know? Rather decontextualised as placed here!

It’s presented in the article as a working compilation that the authors have built up over the past half-dozen years or so.

Compiled based on what? Conversations with people they’ve bumped into? If so, that’s not really rigorous social psychology…

You’re right, it’s not. But they aren’t presenting it as rigorous social psychology either. It’s just a list of terms they have seen trigger misunderstanding. No one is suggesting it’s a peer reviewed opus: just two authors’ insights. Take it or leave as you see fit. 🙂

Language is a code and each grouping develops their own vocabulary that it obvious to them but often impenerable to outsiders (think teenagers, hip-hop, doctors).

The funny thing about communication is that it is what is received that counts, not what the sender sends. The “better choice” column is a great illustration of how you can improve communciation by thinking with the ears of the receiver.

Speaking of obfuscation, how might I interpret “impenerable?”

I’m pretty sure that’s a typo – he means “impenetrable.”

That’s my point. I’m sure that scientists are sure that what they write means what they think it means.

I wonder what Donald Rumsfeld would have to say.

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

I love this Rumsfeld quote – for a guy who was in many ways a warmonger and spinmeister, this particular quip is full of epistemological wisdom.

Do you quote it here as an example of effective or ineffective communication? (Sorry I have to ask – another example of information failing to cross the communication divide, I guess!)

You probably didn’t even notice my intentional (mis)use of the word “obfuscation.”

obfuscation – the activity of obscuring people’s understanding, leaving them baffled or bewildered (Note that this definition doesn’t include the word intentional or unintentional.)

Obfuscation should never be used when communicating with Your Average Joe, namely me. Hell, I didn’t even know what it meant until I looked it up! My vocabulary easily fits on a postcard, which is why they won’t let me into places like MIT or Stanford.

As for Rummy and Dummy, life has been dull since Obama came into office. Sure miss those malaprops. Now I really should be thinking about how all those polo bears are gonna cope with rising sea levels.

Sure, I noticed it.

But what’s your point with the Rumsfeld quote? Are you saying he’s intentionally obfuscating something? Or are you using this quote as an example of clarity? Sorry, your meaning isn’t getting clearer to me with the response you just left. Are you trying to prove a point by being deliberately vague? Maybe I’m just dim.

Rumsfeld was a perpetual liar. I claim that he was intentionally obfuscating to throw the journalists off-guard. He claims otherwise: http://www.rumsfeld.com/about/page/authors-note

I see.

While I agree that Rumsfeld hid the truth habitually and detrimentally, the quote you cited is my #1 favorite thing he ever said. I think it’s brilliantly expressed – the repetition of “known” catches one’s attention and draws one into thinking about the issue in question – what varieties of things we don’t know. I guess it won’t appeal to everyone, but I really like clever word play like that – perhaps not a sterling example of communication, but a nice example of the bigger picture of understanding the (incomplete) state of our knowledge. It’s the one thing that he ever said that I remember and repeat as a “truism” about human understanding.

Thanks for clarifying.

re: Rummy.

Even a broken clock is right twice a day.

Callan (sorry; I cannot see how to reply farther down the thread where this would be more appropriate), please don’t give Rumsfeld too much credit. That “unknown unknowns” concept was a crucial element of problem-solving methodology, even for such lowly technical staff as I, when I worked for a Defense Department consulting firm, lo these several decades ago.

Rumsfeld was merely parroting something that was always a consideration for everyone involved in DoD policy and/or research. And he clearly never considered the implications of the myriad unknown unknowns when he urged the invasion of Iraq; for him those were evidently just words with a nice ring to them, not a rule to live by.

Hey you made it onto Boing Boing! They also link to a google doc being compiled by Southern Fried Science link

Thanks for the update, Katie. For those who are interested, here is the post on Southern Fried Scientist, and here is the post on Boing Boing.

Great post, Callan. How about adding “theory” to the list, too.

“Theory” is there already – fifth one on the list.

Given the current political climate (“climate”, another loaded word), language usage is especially important. As is obvious in the public debate, there are a number of groups with an interest in deliberately distorting scientific terms to make a political point. “Theory” is a case in point, leading to bumper-sticker logic suggesting “my guess is as good as yours”. Scientists writing for publications and/or speaking in interviews and seminars aimed at general-interest audiences would do well to consider using the alternate word choices, and “distortion-proof” their language on controversial issues.

Chuck, I don’t think that scientists communicate clearly with others in their same field, much less with others in a different field, other scientists in another country, or the general public. In grad school we reviewed about 60 impressive journal articles on structural geology research that were, in detail, highfalootin gibberish. And there was the Archeology paper I reviewed a couple of years ago on the petrography of a Roman-era building material where the author used the descriptive terms for soils – for the first and second readings I thought that he was describing a coarse-grained concrete, when in fact he was talking about a fine-grained plaster. And, I recently translated a number of engineering research reports from South Africa, which is an English-speaking country. They don’t actually define and use some engineering terms the way we define the same terms in the US, it just seems that way for about a week. I’m sure that people don’t often communicate fundamental principals to each other. We only communicate general impressions. The closer that one pays attention to what the other person said, the less one one understands just what the other person talked about.

Thanks for posting this. Medical science offers many examples, too, such as a positive test (not necessarily good) and a progressive illness (not a disease that strikes liberals). Then there’s “elegant,” a science buzzword that evokes experiments done in black tie and pearls.

Congrats, Callan, you got linked to by Bad Astronomy! Hope you enjoyed Minneapolis while you were here. I wish I could have showed you our Institute for Rock Magnetism!

Hassol & Somerville’s excellent article is available in full online at: http://climatecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Somerville-Hassol-Physics-Today-2011.pdf

The bottom line, of course is: If you want to communicate, you can’t speak in a foreign language (e.g. jargon). Or — in the words of spinmeister Frank Luntz), “It’s not what you say, its what people hear.”

Actually, nobody illustrates this better than Gary Larson, in this classic Far Side cartoon:

http://www.climatebites.org/tools/172-What-you-say-vs-what-they-hear

—————–

P.S. A few additions to the table above:

Greenhouse gases (some weird smell?)

vs. Heat-trapping gases

anthropomorphic (foreign cultures?)

vs. “human caused” or “man-made.”

Here’s my short video attempt to talk about carbon and climate to a broad audience:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85TQHzS88L4

Peter — I met with a park ranger who heard your recent banana-coal new-old carbon shtick at NSP in Shepardstown a couple of weeks ago. He found it very effective; it left an impression.

Brilliant choice of fruits — just saying the word “banana” makes people start smiling!

Video is great — short, snappy and distilled to the essence.

I concur – well done, Peter!

You could add ‘like’ to the list. I recently heard of a lesson observation where the teacher was explaining to a child that something happened “because like charges repel.”.

The child assumed that the teacher inserted the word “like” into the sentence as a verbal tic, rather than it actually having any meaning — and seemed to understand that the phenomenon in question happened, like, “because charges repel”.

This problem *isn’t* limited to scientific “jargon”. It’s about (some) people lacking a basic grasp of the language.

There are plenty of non-technical examples where sentences are misunderstood by the hard of understanding, or conversely where they construct a sentence that means something other than what they meant. Double negatives are a distressingly common example, but there are many more.

“It’s all Greek to me,” said the Anglo-Saxon. Or perhaps he meant “It’s all Latin to me.” Back in the days before literacy, the educated communicated mostly in Latin, presumably to keep their subjects from their subjects. Many excellent books have been written on clear and concise communication, and one of their common themes is, “Don’t use five or ten-syllable words where one or two-syllable words will do.”

Scientists are enamored of their extensive Latinate vocabularies, and they love having their hard-earned Latinate vocabularies enamored by others. In other words, when I use big words, people will think I’m really smart.

Let’s take the sore subject of Climate Science. “Enough with the Climate Science lectures already,” says Your Average Joe. Why? Because their scientific jargon doesn’t make any sense. Visit http://www.skepticalscience.com/ and see how long you last there.The climate scientists over there aren’t writing for the general public, they’re writing to impress each other. Their articles aren’t going to motivate Your Average Joe to do anything but go on to another website.

Climate scientists don’t know how to communicate with the general public. And rearranging a few words to “Communicate the Science of Climate Change” to Your Average Joe ain’t gonna cut it. They need to relearn from kindergarteners the art of drawing simple pictures that Your Average Joe can visualize and respond to.

Here is a headline and first paragraph from the main page of the above website:

“Sea levels will continue to rise for 500 years”

“Rising sea levels in the coming centuries is perhaps one of the most catastrophic consequences of rising temperatures. Massive economic costs, social consequences and forced migrations could result from global warming. But how frightening of times are we facing? Researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute are part of a team that has calculated the long-term outlook for rising sea levels in relation to the emission of greenhouse gases and pollution of the atmosphere using climate models. The results have been published in the scientific journal Global and Planetary Change.”

Sea levels will rise for 500 years? Results published in the scientific journal Global and Planetary Change? What the…

Couldn’t they have given some examples of the consequences, such as on this website? http://www1.american.edu/ted/ice/dutch-sea.htm

“With 41,526 sq kilometers, the Netherlands supports a population of just under 16.5 million people, making it one of the most densely populated countries in the world. If flooding occurs on a mass scale many people will be displaced from their homes and workplaces. Rising sea levels could wreak havoc on the Dutch way of life. The people, economy, and land itself, would be swept away, costing the Dutch their livelihood and possibly their lives.”

Or on this website? http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/bangladesh-in-dread-of-rising-sea-levels-687400.html

“Flying low over the Ganges and Megna rivers’ flood plains – the world’s largest delta – the threat to Bangladesh of global warming and the disaster unfolding for its impoverished population is all too apparent.”

This introductory paragraph is so important, it was repeated!

So which of the two types of information about rising sea levels is Your Average Joe likely to read and heed? Write it right and you won’t need a conversion table between climate scientists and Your Average Joe!

To get back to misunderstanding the words used in climate science, how about CARBON. The first, and maybe even the last, impression that people get when carbon is mentioned is black soot. In reality, climate scientists are talking about carbon dioxide, a colorless, odorless gas. Even though the word carbon may have been picked for political reasons, it is imprecise and detracts from the science in the argument.

Carbon cycle scientists are not just talking about CO2! I’ve recognized the problem you raise and have been experimenting with ways to talk about carbon in all its forms. See my video linked above. I don’t claim to have solved all communications issues for all time and welcome suggestions for how to talk about CO2, CH4, CO, CO2e, black carbon, carbohydrates, DOC, DOM, CDOM, and CaCO3, without causing the audience to run screaming from the room. Or just fall asleep.

I believe people need to know less about the different forms of carbon and more about how greenhouse gases work. That’s not an easy subject, and you folks can shape my drivel into something that school kids could understand.

I live in a solar-heated house with no furnace. My extensive set of south-facing windows are designed to pass visible and ultra violet (UV) light but reflect infra red (IR) light. Today it is 40° F outside and 72° F inside. The sun’s incoming radiated UV and visible light energy heats up objects and me inside the house (excites our molecules) and we try to settle those molecules down by radiating (sending back) IR to everything within our view. All that cool stuff outside would be happy to take a lot of our IR energy through those “greenhouse gas effect” windows, but they get in the way. They readily absorb our IR energy and send (reflect) much of it right back to us, making me feel better when it’s cold outside, but less comfortable when the indoor temperature reached 82° F late August.

I would propose two simple experiments. Start with a big sheet of glass that passes most UV light but absorbs and radiates IR light. That would be somewhat like one of my windows.

Shine a UV light on a subject at a fixed distance away, with and without the glass inserted between the light and the subject. Ask the subject to comment on the difference in sensed heat intensity between the two cases. How much effect did the glass have on the UV light? How much did the glass heat up from the UV light?

Then repeat with the IR light. What are the conclusions? If the glass reduced the IR light intensity felt by the subject, where did the energy go? How much did the glass heat up? How much of the IR energy did the glass reflect? How much energy did the glass pass on through?

How might one explain in simple language how this all works? For some answers, we might start with “Six Easy Pieces” by Richard P. Feynman and move on to “Six Not-So-Easy Pieces” in desperation.

The second experiment won’t be so easy. Explain that the layer of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere is somewhat like that sheet of IR-blocking glass. The subject needs to understand that some molecule types readily absorb and radiate UV energy and other molecule types readily absorb and radiate IR energy. Also, many atom types will readily absorb UV energy and radiate IR energy, but not the other way around. Again the why and how of this may be over most people’s heads. Do we need to get into quantum physics? There are some neat CO2 and CH4 demonstration videos on the Internet.

The earth’s atmosphere has four basic layers, the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere, in that order from ground up. http://www.vtaide.com/png/atmosphere.htm The sun sends out lots of UV and some IR. Experts say that the ozone layer in the stratosphere absorbs much of the UV, and most of the rest passes right on through to hit the earth. These UV rays are then absorbed by liquids and solids and can make some stuff get really hot, like “the parking lot surface was 160° F,” or “you could fry an egg on my car hood.” But the UV energy doesn’t make most of these objects hot enough to radiate UV back, so they, in turn, return lots of IR energy back into the troposphere where most of the greenhouse gases reside.

Now the excess CO2 and CH4 will gladly get excited over all that IR coming up from below and absorb much of it. Whatever IR the greenhouse gasses absorb will have been interrupted on its way out into space. The newly excited greenhouse gas molecules will then heat up and warm the lower atmosphere, but more significantly a good percentage of those heated molecules will cool back down at night and send a significant amount of their new-found energy right back to Earth for another go at our air conditioners. Ouch!

The bottom line is that excess greenhouse gasses mostly ignore the incoming UV radiation from the sun, but they prevent much of the IR radiation heat energy from escaping back out into space. They cause the earth and lower atmosphere to slowly warm up, but probably have little or no effect on the temperature of the outer atmosphere.

Over the millions of years, Earth has worked out a happy medium between greenhouse gas concentrations and energy accounting. Now, in a course of 150 years, we have sent that equilibrium into a tailspin. Like a giant passenger plane in a tailspin, climate scientists have no experience predicting the nonlinear response characteristics of our world in a tailspin.

They might as well have in included “improbable” or “unlikely”, which the public seems to think means “1 in a hundred” whereas it’s typically “1 in a billion”

Here is an excellent reference for any scientist’s writing shelf: http://www.amazon.com/Make-Your-Words-Work-Writing-/dp/0595174868/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1319114589&sr=1-1 See also http://www.garyprovost.com/

Here is a brief excerpt from that book:

‘Once upon a time I wanted to learn about the human brain. On one of my exciting trips to the Laundromat I stopped at the library and grabbed a couple of brain books off the shelves without browsing through them. A few days later when I found the time to sit back and look at them, I devised a simple test for deciding which book to read. I picked up the first book, flipped to a page at random, and stabbed my finger at it. I landed on this sentence:

‘ ‘”But does the greater spontaneity and speed of assimilatory coordination between schemata fully explain the internalisation of behaviour, or does representation begin at the present level, thus indicating the transition from sensori-motor intelligence to genuine thought?”

‘Then I grabbed the other brain book, flipped it open, poked in my finger, and landed on this:

‘ “If a frog’s eyes are rotated 180 degrees, it will move its tongue in the wrong direction for food and will literally starve to death as a result of the inability to compensate for the distortion.

‘Which book do you think I read?

‘Which book would you have read?

‘Both were written by experts on the subject, but unless the reader is also an expert, there is no contest in the fight for reader attention. The second one is just better writing.

‘The author of the second book used visual images to put what he understands into a form that I understand. I can see that confused frog’s eyes rotating and his tongue shooting off in the wrong direction, while assimilatory coordination stuffed into a sentence with schemata, internalisation, and sensori-motor intelligence leaves me more confused than even that frog.

‘The second author also won me as a reader for the same reason that you will make more friends in Burundi if you brush up on your Swahili. He spoke to me in my language. The expert who wrote the first sentence wrote to me in his own language.

‘The author’s use of visual images and accessible language should establish more firmly in your mind something that you already knew when you picked up this book: Style does make a difference. It’s not just what you write that matters; it’s how you write it.

‘Although too many editors these days emphasize the story, the content, the subject, over the technical abilities of the writer, good writers can make any subject interesting, while incompetent writers can make anything dull.’

Roger — I actually think your raise some very important points. We should all “eschew obfuscation,” right? 🙂

Reminds me of the classic Far Side cartoon featuring Gary Larson’s dog Ginger and her owner, which I happened to clip last night for a post on this very point ( http://www.climatebites.org/2011/10/20/its-not-what-you-say-its-what-people-hear/)

Your reaction to Ginger (and the rest) would interest me!

We’ve made the companion piece on climate change free next to it, in case you haven’t read it yet.

Paul — Since I’m a newbie here, I seem to have lost track of this thread….which “companion piece on climate change” were you referring to, and where is it posted?

Thanks

If you want to improve communication, PowerPoint is a crappy way to do that.

Duly noted. It’s also ubiquitous. English may not be the most efficient language to use, either, but the contingencies of history, technology, and linguistics leave us with these as our default options.

Agreed, and if used wisely, which is rarely is, it can be a good tool.

I’m old enough to not only remember presentations before PowerPoint, but to have used a typewriter for composing slide presentations. PowerPoint is at least two orders of magnitude better for presentations. But, it is no better than the training and artistic skills of the person composing the presentation.

My 2-cents is that PPT can be very useful for sharing information, or striking images.

It is very poor for persuasion, or any communication that requires making a personal connection with the audience.

Some say PPT crashed the Shuttle. That’s hyperbole. But point taken.

Seth Godin’s ebook Really Bad PowerPoint is now 6 years old. Unfortunately, the lessons it teaches are still lost on most presenters: Cut down on your words. Sell, don’t tell. Use pictures to invoke emotion. Slides back up your voiceover, they don’t replicate it. Today, PowerPoint has replaced the Company Memo as the communications tool of choice, with poor results. As product managers, we must be excellent communicators.

http://bit.ly/vOUGZX

Interesting, Callan. I’ve been discussing the word “parameter” with my undergrad graphic design students; “constrain” would fit the public meaning and “limitation” the better choice.

—a

For biologists a couple others come to mind

1) Tissue –

Public meaning Klennex

Better worlds

samples

probably better to specify the type of samples

plant samples, heart samples, leaf samples, etc

2) Sections

Public meaning the group you work with

Better word

Dissections of whatever

How is “vicious cycle, self-reinforcing cycle” equivalent to “positive feedback or “self-reinforcing cycle”?

You’re right, words do matter. But not those words.

Science strives very hard to be accurate with its language. It’s usually the public, media or those with hidden-agendas that misuse or twist it.

And for “Better Choices” to be universally accepted, a consensus with the entire scientific community would have to be achieved… and not by one blogger.

Hi Daxx,

I’m confused what you’re asking. You’ve got “self-reinforcing cycle” on both sides of your question of equivalency.

Anyhow, a good discussion of that particular linguistic quibble is in this post by Kim Kastens.

The question here is not whether these words are scientifically accurate, but whether they mean the same thing in the minds of the public as the minds of the scientists. I think the verbs you offer, “misuse” and “twist,” imply intentional obfuscation. The whole point of this list

Lastly, it should be reiterated that this list is not mine — the “one blogger” you’re referring to? — but a compilation from more than a dozen years of research by Somerville and Hassol. Check that link (the original article) to get the backstory, if you’re interested.

Thanks for opining,

C

The scientific community has its own use of certain words they use to communicate and understand each other, these words are then adapted by the general public for their own use in daily life. Using a better/ different choice of words simply means that in another few years, there will be another table up there.

Interesting glossary there. It’s weird to think how words can have such different meanings in the world of science and in regards to context in general.