My wife and I journeyed out to Paw Paw, West Virginia, yesterday, then crossed the Potomac to enter the southern edge of Maryland.

The purpose of our jaunt? Gigapannery! (That’s what I’ve got my sabbatical to do, of course) We walked along a short stretch of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal’s tow path, and then entered the Paw Paw Tunnel, a tunnel 3/5 of a mile in length, lined with six million bricks, that takes the canal through a mountain. The tunnel took 14 years to build due to the unstable nature of the rock underlying the mountain (the Devonian Brallier Formation shale), and nearly bankrupted the Canal company. Why would they bother with a tunnel when the other 183.9 miles of the Canal are out in the open air? It has to do with the history of the Potomac River drainage: the Potomac is a rejuvenated river along this stretch, meaning it developed a meandering form, then cut down to lock that sinuous shape into a bedrock “canyon.” When building the Canal, the engineers got to Paw Paw and breathed a sigh of dismay. They were faced with a difficult choice: To get from point A to point B (see map below; contour interval 20 feet), they could either follow the looping shore of the Potomac River (which would mean a longer C&O Canal), or they could take a shortcut by tunneling through the mountain (which would be shorter but maybe a little more work).

So that’s why they decided to build the tunnel: it was shorter to get from point A to point B. Turns out, though, that it wasn’t all that easy.

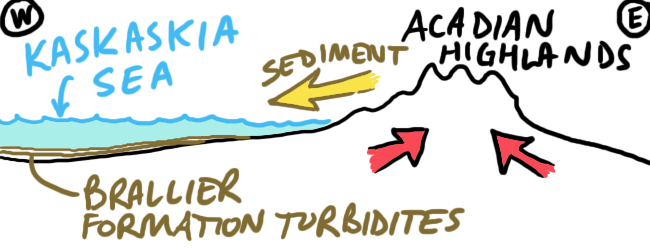

Why was the tunnel such a hassle? First off, consider how the rock formed, and then deformed. It was originally deposited as layers of mud shed off the second Appalachian mountain-building event, the Acadian Orogeny (~360 Ma). As mountains rose to the east, they shed sediment which was transported west into an epeiric sea, the Kaskaskia Sea. There, they were deposited by turbidity currents. Later, once this mud had been lithified into shale, we would call it the Brallier Formation.

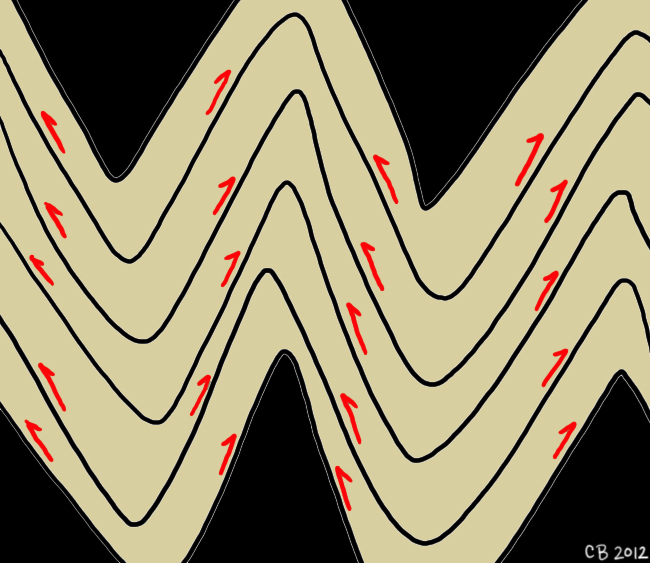

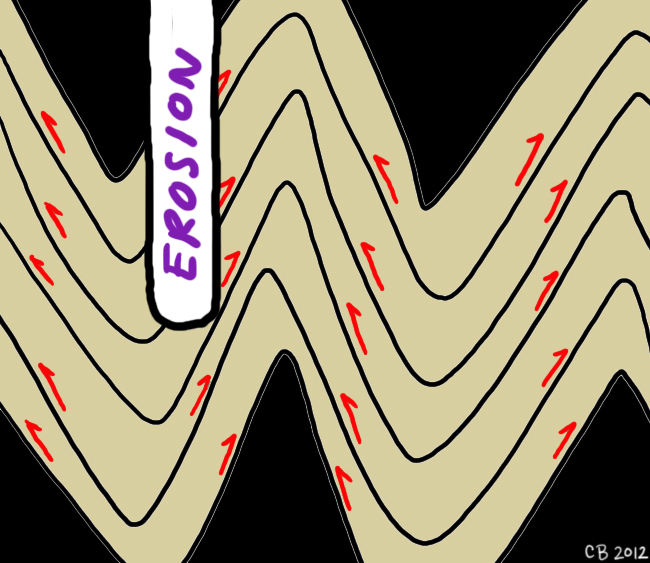

Later, during the ultimate phase of Appalachian mountain-building, the Alleghanian Orogeny (~300 to ~250 Ma), these Acadian deposits got folded and faulted. For the present discussion, consider only the folding. The layers crumpled up, partly by having each layer slip relative to the layers above and below it. The bedding planes became small “faults” in this scenario of flexural slip:

Because a layer could slide bodily relative to its neighboring stratum, slickensides developed on the surface of the beds, sometimes overprinting ripple marks, tool marks, and other primary sedimentary structures. Check out these lovely crystal fiber lineations with upward-facing steps:

So the layers slid relative to one another on slick surfaces, and then came to rest in a variety of orientations. Later incision by a stream (and then augmented by the C&O Canal company) carved the valley called Tunnel Hollow.

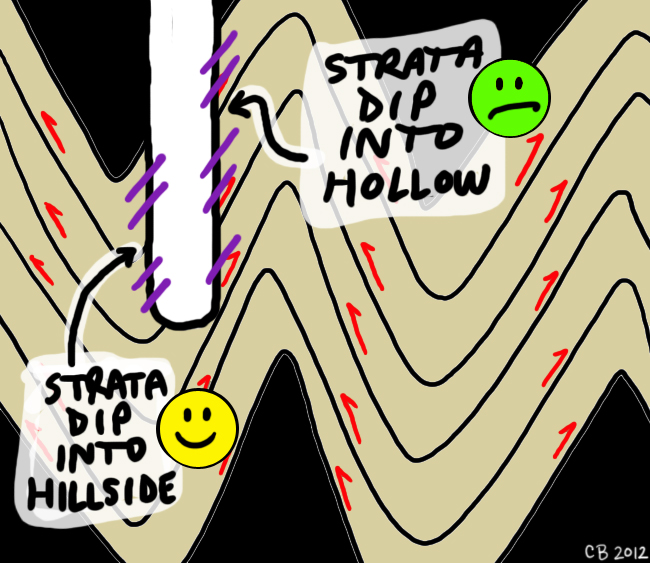

That caused a problem – as the strata on the two sides of the hollow now have very different susceptibilities to rock slide. One side of the valley has strata dipping into it, while the other side has the strata dipping away from it.

The side with the strata dipping into Tunnel Hollow is the problem: With nothing to support them from below, slabs can detach and slide downhill into the empty space below. Woe to the C&O Canal worker who was standing in the way!

With rocks like that – big slabs poised to come crashing down any time, no wonder it took the C&O Canal company so long to dig the tunnel. Modern recreationalists using the Canal tow path are somewhat safer, as pins have been drilled into the layers to lock them in place. You can see these giant “safety” pins in some of the images we took yesterday.

And now, without further ado: Here are the results of our trip, four explorable, annotate-able GigaPans…

The downstream end of the Paw Paw Tunnel (see if you can spot the anticline):

link

The upstream end of the Paw Paw Tunnel (see if you can spot ripple marks):

link

(…or the torso of a reading instructor from Montgomery College who happened by with her friend as the GigaPan was nearing its conclusion!)

Slickensides on a slab of Brallier Formation shale (see if you can find the lens cap I included for a sense of scale):

link

Slabs of rock that have slid down the face of tilted beds of Brallier Formation, thankfully before your ankles got in the way (see if you can spot the pins used to hold the big slabs of rock in place, high above you):

link

Really cool post. Really cool geology. Great gigapans. The gigapans are not marred by variable exposure like some previous ones, although ISO is still varying among shots. Can you turn off Auto ISO? Might as well turn off Auto White Balance too. I look forward to many more gigapans with NO BLOTCHES.

Chris, I’ll see what I can do. I’m a photographic novice – some things come naturally, like framing a shot, but the technical variables are still a bit fuzzy to me. Thanks for the prompt. I’ll educate myself today on ISO and White Balance settings in my new camera.

Love the virtual field trips. Thanks.

Now, way off topic: paw paws. I love them! I haven’t eaten one in… probably, 20 years. Apparently, they were a staple food source for Appalachians back in the day. In the hit 60s show, “The Beverly Hillbillys”, Granny(Irene Ryan) makes a reference to pickling the fruit in one of the episodes(I was a kid, so I can recall when or where).

A sport, of sorts, we used to play, was to get the uninformed(city kids) to have a taste of persimmons just before they were ripe(mostly orange, but some dark). All agreed that the fruit was good, and then they puckered.

To be fair, a ripe persimmon is something everyone should experience- sweet and succulent.

Paw paws: I have never eaten a pickled one, but ripe, they look like a giant peanut and taste like a banana, but have the texture of a pumpkin… Yum!

They are delicious! I’ve only had one once, but it was memorably good.