Hume Vineyards is a vineyard (grape-grower) and winery (wine-maker) in Virginia’s Blue Ridge province. I journeyed there yesterday on the fall field trip of the Geological Society of Washington. Joining me were a crew of about 20 people. Think of them as wine enthusiasts with a geology problem.

We were interested in the question of how the rocks, soil, and climate influence the qualities of the wine produced here – the French concept of terroir (pronounce it “tare-whah”).

Virginia’s wine-making industry has really come into its own over the past decade (there are now 210 wineries in the Old Dominion), and now produces some wines that are competitive with wines produced in classic winemaking regions like California. It’s more challenging to make wine in Virginia because the climate is wetter and the growing season is shorter (It takes ~210 growing days to make a Cabernet Sauvingon, for instance, but Virginia typically yields only 180 to 185 per year.) The humidity matters because growing grapes for wine isn’t like growing tomatoes in your garden – you actually want the grapes to struggle a bit, and produce berries with less water and more concentrated sugars. So Virginia isn’t as renowned for wine as France or Chile or California, but clever, dedicated vintners here are figuring out which grapes grow best in Virginia, and how to turn their juices into the best wines they can be.

Our goal was to visit two wineries on the trip, situated in different geologic settings, and compare the resulting products by tasting them. We began in the Blue Ridge province, in the central part of the anticlinorium near the village of Hume, in the basement complex.

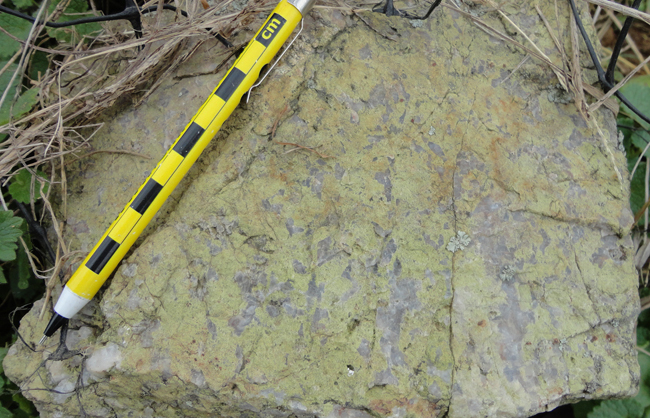

Here’s an outcrop on the Hume Vineyards property:

If you stroll over this little bald spot, you’ll find that it’s composed of a very distinctive rock type: a granite!

This is the Laurel Mills Granite (U/Pb dated to ~729 Ma). It’s part of the Robertson River Igneous Suite, a collection of anorogenic granites associated with initiation of rifting of the Rodinia supercontinent. We don’t understand the RRIS all that well (read more on page 20 of Southworth, et al., 2009), but it’s clearly cross-cut by feeder dikes of the Catoctin Formation (~560-570 Ma) flood basalts, which were erupted when Rodinian rifting really got cranking, and the Iapetus Ocean opened up.

Here’s a xenolith in the alkali granite:

Now take a look at this photo, and see if you see anything new:

The eagle-eyed structural geologists among you will pick out some dark shear bands in there, cross-cutting the more-or-less equigranular magmatic fabric. Here’s a nice shear zone with anastamosing mica domains wrapping around quartz-feldspar domains at right, and merging into an asymmetrically-developed shear zone at left:

More of these anastamosing (braided) small shear zones:

They remind me very much (in size and distribution, if not outright sexiness) of the suite of small shear zones I observed a year ago in the Grassy Portage Sill of southern Ontario.

Here’s a big spider-web of these shear bands deforming the granite:

These ductile shear zones are interpreted to be Alleghanian in age (~300 Ma), deformation associated with the final closure of the Iapetus Ocean and formation of the supercontinent Pangaea. They strike between due north and east-northeast.

Both the shear zones and a series of minor veins and aplite dikes are in turn cross-cut by late-stage brittle deformation. Here and there, small faults offset these strain markers a few centimeters.

Further along strike of this same shear zone / aplite dike couplet, I saw one more small fault. Can you spot it?

There was also some epidotized granite – the sort of thing we would call unakite if it retained any appreciable potassium feldspar.

The granite imparts an acidity to the soil, one of the variables we suspected might influence the grapes grown there. We had a discussion of the various terroir considerations in a barn where the winery had set up a tasting for us. Here, trip leader Bill Burton discusses the geology of the Blue Ridge basement in the vicinity of Hume Vineyards:

Bill points out our afternoon destination: the Massanutten Synclinorium of the Great Valley subprovince of the Valley & Ridge Province:

In contrast, he points out the Robertson River Igneous Suite (peach pink) intruded by feeder dikes of the Catoctin Formation (green stripes) in the vicinity of Hume:

The focus begins to shift…

We sampled six wines at Hume: two whites (a Seyval Blanc and a Viognier), three reds (a Chambourcin called “Rock Star,” a Cabarnet Franc, and a blend called “Detour”), and a white dessert wine called Vendange Tradine (“Final Harvest,” I guess) which I liked very much. It had 5% residual sugars, which seemed like just the right amount – not too cloying or too dry. I bought a bottle of that to bring home for Thanksgiving dinner.

I don’t usually choose whites when I’m drinking wine. Like a lowbrow dilettante, I’ll even opt for red when eating fish or chicken. So it was surprising to me to discover that I really liked the whites I tried at Hume: the Viognier tasted very clean, and the pourer pointed out that many Virginia Viogniers are over-oaked. (What she literally said was, “They oak the crap out of them!”) In contrast, the Hume Viognier (the 2011) was racked 75% in steel vessels, and only 25% in oak. This meant we could taste more of the grapes, and less of the wood’s astringent flavor.

The reds weren’t as great to my palate, and that’s typical for the reputation of red wines from Virginia. The Chambourcin came from the red-leaved vines featured in the photos at the start of this post. It was very spicy, but it had an aftertaste I didn’t love. The Cabernet Franc was good – this grape grows well in Virginia’s climate, but it’s apparently tricky to craft a wine with it once you’ve harvested the grapes. The other Cabernet Francs I’ve tried (on other wine-tasting excursions) have left something to be desired, so I was pleased with the reception this one got on my tongue. Our pourer noted that the further south you go in Virginia, the “grassier” the Cabernet Franc becomes.

And, with the tasting and the geology both concluded, our posse decamped and set off to the west, headed for the Valley & Ridge province. Adios, Hume Winery, and thanks!

Thanks so much for this great post.

As a “lowbrow dilettante” of geology and a sixteen year veteran of the wine industry, I really appreciate the photos and descriptions. They do a great job illustrating the geology for someone like me.

By coincidence, I just finished reading the section of John McPhee’s book “Assembling California” where he and Eldridge Moores taste their way through the geology of the Napa Valley. It’s a great read for anyone interested in both terroir and terrane.

Great book – I remember that section of the narrative well. “A Mohorovicic red…” 🙂

Thanks for this interesting read! I’m another geology dilettante who started reading your blog when you reported on your South African experiences. A note on your “struggle & more sugar” comment: In SA’s warm climate we actually have a problem with too much sugars – translating into high alcohol wines. The higher and variable concentrations of all the other aroma and taste components in struggling or “differentially exposed” grapes are of course also very important.

I’m a keen earth cacher and have developed a “Terroir & geology” earth cache near Stellenbosch, which you might be interested in, see http://www.geocaching.com/seek/cache_details.aspx?guid=c131cdfe-0d2f-4f23-92a6-f5bd8c28e06c

It’s like anything, I guess — too much or too little is harmful. Gotta aim for the sweet spot. Thanks for the Earth cache link!