You’ll recall that last weekend, I went on a geological wine tour of northern Virginia with fellow winos geologists from the Geological Society of Washington. After a pleasant foray to Hume, we went west, to the western limb of the Massanutten Synclinorium, and North Mountain Vineyard and Winery, near Toms Brook, Virginia.

This location was chosen for two reasons: (1) it’s on the other side of the Blue Ridge Thrust Fault, in the early Paleozoic sedimentary strata of the Valley & Ridge province (as opposed to the igneous rocks that underlay our previous stop), and (2) it’s partly owned by a USGS scientist, John Jackson. He’s the chief wine honcho, making all the blending, fermentation, racking, and storing decisions.

Here’s John giving an overview of the geology underlying his land:

GSW President Chris Swezey is the fellow with the hat to the right of John:

Then Dan Doctor (also USGS) took over, discussing the carbonate strata of the Shenandoah Valley, his specialty as a mapper with Survey.

Behind Dan, you can see Larry Meinert, a geologist who has a substantial amount of expertise in viticulture and enology. He even blends and bottles his own wines – with grapes purchased from other people’s vineyards. Larry is also the co-editor of a book I think I’ll need to read: Fine Wine and Terroir: The Geoscience Perspective.

(Readers in the DC area might want to hear Larry speak on this topic at an upcoming presentation at USGS headquarters in Reston.)

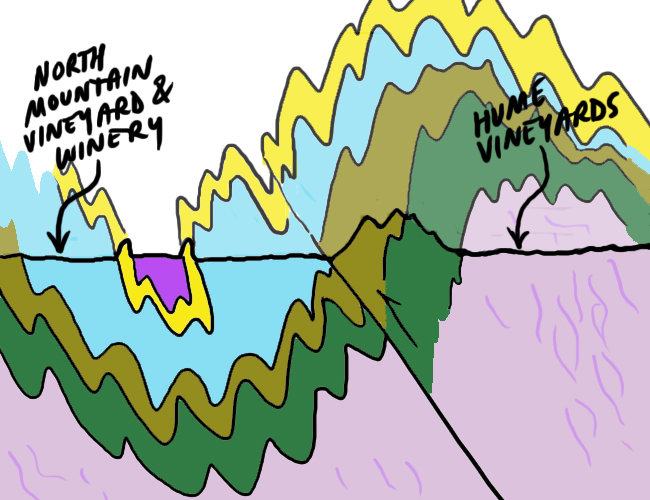

Dan reminded us of the aim of the field trip: to compare the wines grown on two very different rock substrates. A broad-brush picture of the trip, in cross-section, would look something like this:

Perspective in this cross-section is towards the north-northeast. The Blue Ridge is on the right (~east). You can see Hume Vineyards on the Blue Ridge basement. North Mountain Vineyard and Winery, on the other hand, is towards the left (~west), in the Great Valley subprovince of the Valley & Ridge province.

The strata under the vineyard are Cambrian-aged carbonates of the Conococheague Formation. Here’s an outcrop:

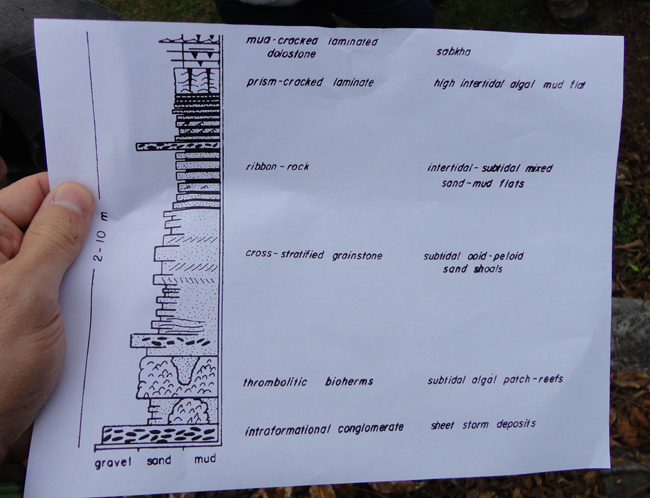

Part of the Conococheague limestone is characterized as “ribbon rock”: interbedded calcitic sands and dolomite silts.

These are interpreted as being laid down in intertidal or shallow subtidal environments.

In places, the Conococheague has lovely small ooids in large numbers:

Zooming in:

We also saw rip-up clasts – a carbonate conglomerate of sorts. These are the signatures of higher-energy waters invading the depositional system.

In the same layer as the rip-up clast conglomerate, we observed stromatolites:

You can see the rip-up clasts to the left of this big stromatolite “cabbage head”:

This is thought to be the basal layer of a 2- to 10-meter thick sequence that records shallowing waters. It’s capped by dolostone with mudcracks. I saw dolostone cropping out, but no mudcracks were visible to me at the vineyard.

There are also some stringers of quartz sandstone in there. Here are a couple examples of the float that results from the weathering of these beds:

Calcite cements are often mostly leached away in these blocks.

In fact, we were surprised to learn that the soil at the vineyard isn’t all that buffered by the limestone bedrock. The wet climate has leached away much of the calcite in the soil, leaving a loamy soil dominated by silt.

Inside the lovely winery building, we found our tasting session awaiting…

Here’s where the magic happens: giant fermentation vats:

Elsewhere, oak barrels store wine:

The barrels are made of French white oak, but I suggested that John should rack his wine in Shenandoah County oak – and I happen to have 24 acres of just that commodity, if he’s interested. The locavore angle is insufficient, however, to overcome French oaks’ reputation as “the best” for flavoring the wine. Oh well; can’t blame a fellow for trying, right?

John served us eight wines.

As at Hume, I found that the whites really appealed to me. We tried a Vino Blanc and a Riesling, and both of them had a bold, citrusy flavor. The Vino Blanc was dry, while the Reisling had 1.8% residual sugars – sweet and high acid. Delicious, really.

We also had a blend called Octoberfest. Along with the Vino Blanc and the Riesling, the Octoberfest features a Traminette grape. The character of this grape dominates the Octoberfest. Apparently it sells well as a result. It was fine, but I liked the other two whites better, I think.

John turned our attention to the reds. We began with a Claret (an old English word that he’s allowed to use, apparently, though other Virginia wineries have been told they cannot). It was fairly dry, which isn’t in general my favorite (I like lush, bold, fruity reds), but this Claret seemed very well balanced and I would gladly drink it if someone gave me a bottle.

The classic Virginia choice, the Cabernet Franc (2009), came next. We discussed the Virginia Cabernet Franc situation, and again the message was: The grape grows well in Virginia, but it’s tough to make a good wine out of it. John told us that his philosophy is “Don’t try to make a big wine out of a grape that doesn’t want to do it.” He thinks that a lot of the issue with the weak Cabernet Francs produced by other Virginia wineries is trying to make this grape into a bolder wine than it’s capable of. This results in off flavors, including hydrogen sulfide.

We got a real treat next: another Cabernet Franc – the 2010 season. I really valued being able to compare the 2009 to the 2010 – same vines, same soil, same zymurgy, just a different year. We all agreed that the 2010 was very good. “It’s as big a red as I can do,” John told us. It hadn’t been officially released yet, but when GSW visitors clamor for you to sell them some anyhow, you break out a case and put it on the counter. I brought a bottle home to share with my wife at dinner for the next two nights.

We finished off the “regular” part of the tasting with a Chambourcin, made from a pinot noir grape. My tasting notes say “Bang!” It’s 14% alcohol, but I found it less harsh than other Virginia Chambourcins that I have tried. I really liked it, too. It’s won some awards for North Mountain, and though it was drier than my palate prefers, I’d gladly drink it at dinner.

The denouement was an apple wine, made with apples from neighboring Rockingham County (I think). It tasted like my own homemade apple cider, but a bit thicker, and without the fizz. Flavor-wise, however, I was pleased to taste it, because it reminded me that I have 5 gallons of similar stuff waiting for me at home!

And with that, our field trip concluded. The rest of the GSW posse boarded their bus and trundled back towards Reston, and I steered my Prius back up into the Fort Valley and storm preparations at home.

Thanks so much to Bill and Dan for leading the geological discussions, and to John for showing us such a nice time at North Mountain Vineyard!

Great series! I know zip about wine (I’m a beer guy), but I’m a sucker for carbonate rocks, and those are nice ones!

BTW: I don’t usually nitpick typos, but I see a geo-typo that could confuse some readers: “This is thought to be the basalt layer of a 2- to 10-meter thick sequence…” Basal, I think?

Thanks! Fixed it!

Great post and photos, Callan. Brought back great memories (minus the wine part) of crawling over many outcrops of those rocks. FWIW – I recall Eugene Rader has a great way of pronouncing “Conococheague.”

How does he pronounce it?

All us Hokies pronounced Conococheague as in “league” (“Major League”), but I recall he pronounced it more like “shag” – which I, as an impressionable grad student, thought sounded cooler and more exotic.

I’m in the same league as you, it seems…

Awesome post Callan. It’s hard to beat booze and geology at the same time! This would be off-topic for the blog, but I wouldn’t mind hearing more about your cider, maybe pics and a recipe? I’ve got 10 gallons of local cider fermenting in my basement right now myself.

I actually tried it for the first time yesterday, sharing a couple of pints with my friend whose farm the apples came from. It’s tasty! My first attempt at kegging – seems to have turned out pretty darned well.

“Chambourcin, made from a pinot noir grape”

Chambourcin is a hybrid; pinot noir is pure Vitis vinifera.

Excellent. Thanks for the correction. I’m basically transcribing my notes here, so I appreciate the fact-check.

Is “Shenandoah County oak” red or white?

You can’t make kegs or barrels to hold liquid out of red oak.

The pores are open lengthwise. The white oaks have septa which block the pores.

Try putting a red-oak stick sawn off a board in water and blow air through it.

Good tip.

We have both northern and southern red oak here, white oak, and probably a half dozen less common varieties, too.