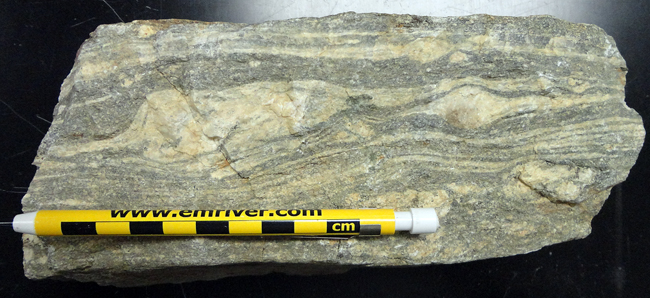

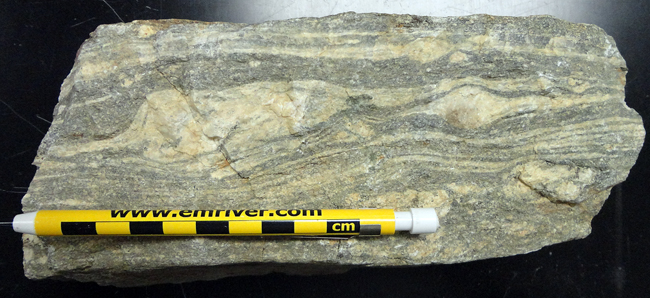

I went into work on the weekend recently, and found two lovely new specimens of mylonite in the lab. Not sure whose they are, or where they came from, but I knew I had to photograph them so I could share them here with you:

I went into work on the weekend recently, and found two lovely new specimens of mylonite in the lab. Not sure whose they are, or where they came from, but I knew I had to photograph them so I could share them here with you:

I know whose they are! Jim brought them back from California.

Purdy!

Superficially, these things could be mistaken (speaking for myself) for augen gneiss or maybe even migmatite. What are the key features that can be used to distinguish mylonite from these other metamorphic rock types, in hand specimens or outcrop? Thanks!

Good question. “Augen gneiss” is an old word for “protomylonite” in my book. Mylonites aren’t “metamorphic” in the sense of mineral reactions having taken place (at least, not necessarily); they are deformational rocks, like a cataclasite or a fault breccia. In my mind, what characterizes mylonitization is some combination of grain size reduction and evidence of ductile flow of some minerals while others remained rigid. There’s a gradation between protomylonite, proper mylonite, and ultramylonite, depending on the grain size reduction observed. But that depends on the context of seeing the undeformed rock – and I don’t have that luxury here. Quartz ribboning and bookshelfed or tailed feldspars, particularly asymmetric ones (as in the second photo), are characteristics I look for in isolated samples like these.

So I’m using “mylonite” sensu lato, and hope to be forgiven for that sloppiness.

Migmatite is another beast altogether – need to show evidence of partial melting (or, granitic injection) to call a rock a migmatite.

Itz a terrific sample…any clue on where the sample came from?