I’m curious to hear what you sedimentologically-inclined readers think of these features:

(with flash)

(with flash)

(without flash)

(without flash)

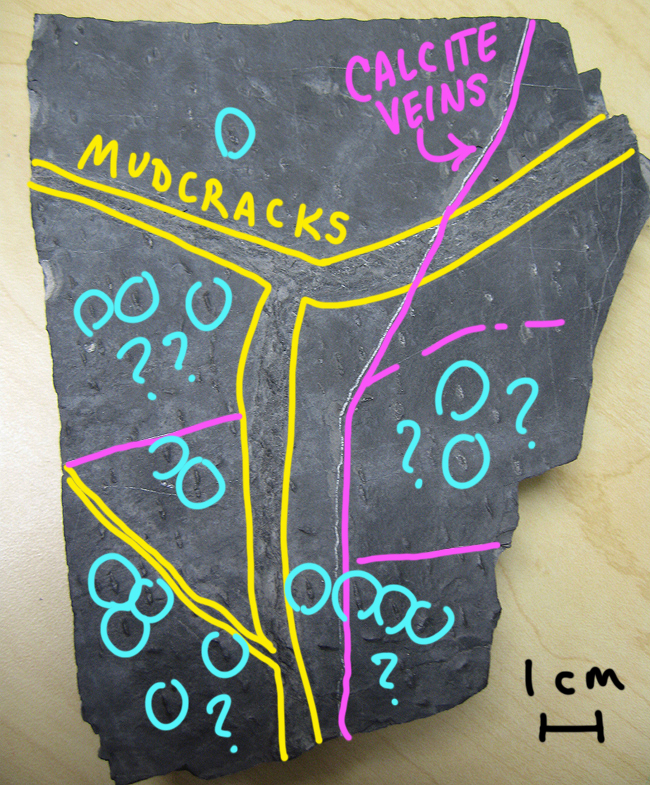

I collected this sample in May on Corridor H in West Virginia, at an outcrop of the Silurian-aged tidal flat carbonates of the Tonoloway Formation. It’s got a nice mud crack (dessication crack) triple-junction (yellow in annotation below). It has a calcite vein that cross-cuts the mud crack (pink). And it’s got lots of little lenses (in the geometric sense of the word) a few mm long, all over the “plates” of the mud cracks (blue). What are they? What do they tell us?

My colleague Joshua Villalobos (El Paso Community College) snagged one then, too. Josh imaged his the other day with a jerry-rigged “macro” GigaPan set up. Here’s the result: It’s not as high-resolution or focused as a MAGIC macro GigaPan, but it does impart an additional perspective on these structures.

I posted a link to Josh’s GigaPan on Twitter the other day, and asked what these things were. I got reactions that ranged from the ichnological to structural, but mainly clustered around the idea of gypsum casts.

Gypsum casts would be something that we would expect to find in tidal flat carbonates – an arid, dessicating environment would encourage the evaporation of seawater and the precipitation of evaporite minerals in the resulting brine. Halite casts are well known from this same outcrop of the Tonoloway.

The key question is then: Why are they all aligned? Any insights?

________________________________

UPDATE: Matt Kuchta has provided a compelling explanation: Syneresis cracks – dewatering structures, essentially. Click the link to the Wikipedia article and compare. Looks like it to me!

Perhaps they are perpendicular to compression as in stylolites.

Look like pseudomorphs after gypsum, like these guys: http://www.southampton.ac.uk/~imw/jpg-Purbeck-Petrography/11PT-Portesham-Pseudomorphs-351.jpg

So far, I can only think of current action penecontemporaneous with crystal growth?

Hmm, that’s pretty compelling, for sure… How can I tease out whether it’s that or the syneresis cracks?

Mike emailed (one more user blocked out of the conversation by the dumb CATPCHA software) and said:

The Lockeia idea is pretty interesting (and I have no experience with them at all), but I copied your top photo, boosted the contrast somewhat, and, overall, some of these things look fairly angular, and more mineral-like than ichnofossil-like, to me. So, I’d still vote for gypsum-pseudomorphs

One other possibility to consider is that they’re trace fossils; they look rather like a bivalve-resting-trace called Lockeia as well as the syneresis cracks and gypsum crystals, though it’s hard to imagine any sort of bivalved organism surviving long in evaporitic conditions–perhaps they were made during a period of greater inundation over the locality? The size range would be about right, too.

Hmmm. Yes, similar shape – but note how in the GigaPan some of them are curved at the tips in non-typical ways. That seems consistent with a crack, but not with a trace fossil… Plus all the Lockeia I was able to find in a Google Image search are ~10 times the size of these ones.

I’m inclined to agree with Jerry Harris on this one. The Treatise (Häntzschel, 1975, Part W, p. W79) describes the ichnogenus Lockeia James 1879 as varying in length “from 2 to 12 mm” which seems to be in the right range for these objects. The photo in the Treatise is a dead-ringer for these things. Hantzschel refers to a paper (Osgood, R.G. 1970. Trace fossils of the Cincinnati area. Palaeontographica Americana, 6(41), p. 281-444; this is an open-access paper available from BHL, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/89422) which gives a very thorough description and discussion (starting on p. 308) and images of Lockeia (starting p. 412). The mechanism of formation–in “calcisiltites” (consistent with your tidal flat carbonates) is interpreted to result from a small clam burrowing down through an overlying sediment and stopping when it tags the top of an underlying muddy bed, thus leaving a small lens-shaped dent in the top surface of the mud bed.

If this is the case, it makes sense that the lenses would have a preferred orientation, as these burrowing bivalves would probably prefer to orient their siphons (inhalent and exhalent) with respect to a current.

Can you see any of these objects in cross-section on the edges of the slab? A good test would be to look, next time you visit this outcrop, for specimens in place, or slabs with pieces of the overlying bed attached. Osgood’s paper shows images of distinct vertical burrows disrupting the horizontal lamination of the deposit overlying the Lockeia traces.

My issue with the syneresis interpretation is that your lenses are so consistently simple and lens-shaped, with never a 3-way junction, and so well oriented. The wiki photo of syneresis cracks, if you click through to the full size images, shows random orientations and lots of 3-way junctions as well as fusion with larger cracks in many cases; this is the sort of behaviour I would expect of any sort of shrinkage cracks; not isolated, completely uniform (in size and shape) and generally oriented dents.

The plot thickens! Thanks for your thoughtful analysis, Howard!

Here’s my contribution to these things. I don’t know what these are, but it would be interesting to get a thin section through the ones in my shot because there is obviously a different mineralogy in the “cracks.”

https://www.flickr.com/photos/deepcaves/15831713631/

I would be very interested in seeing photomicrographs of these features if someone makes thin sections of them, preferably both in the plane of bedding and perpendicular to bedding. Thanks, Beth Haverslew

We made a macro GigaPan of this specimen.

Here it is:

http://www.gigapan.com/gigapans/168752