Last Friday’s fold was one I spotted when out geologizing last Thursday in Edinburg Gap, a wind gap in the western Massanutten Range, one of the main paths of egress for those coming into or leaving the Fort Valley. There, massive outcrops of Martinsburg Formation grace each side of the twisty road, and reveal a totally different ancient world.

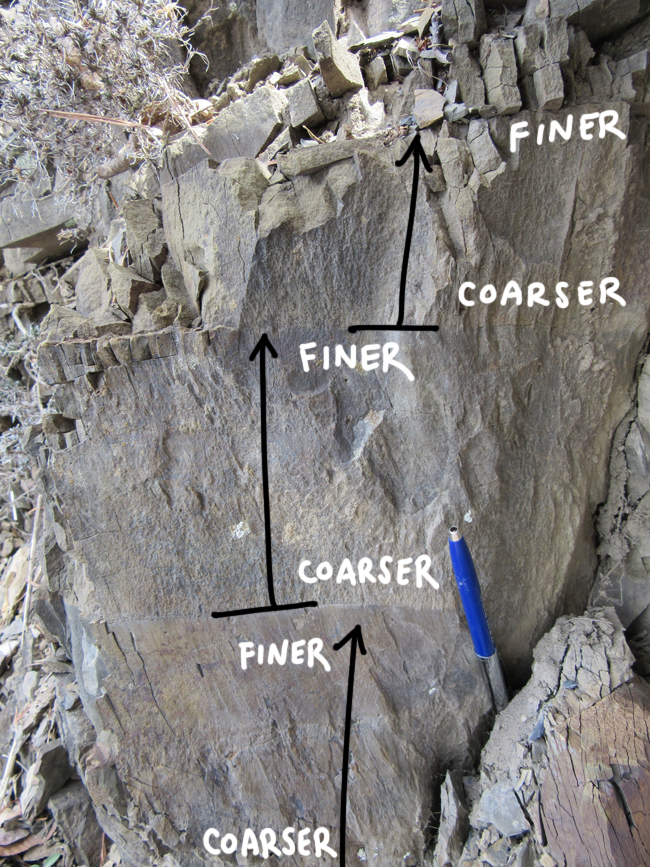

In the late Ordovician period of geologic time, this site was deep underwater, a trough-like basin receiving copious quantities of sediment from the active Taconian Orogen to the east. The sediment was brought out in pulses — underwater avalanches called turbidity currents; that settled out to produce graded beds of shale and graywacke.

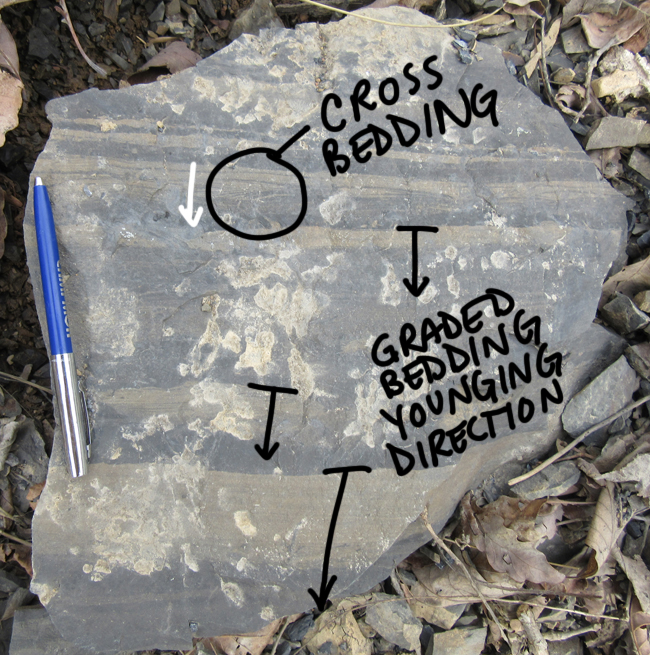

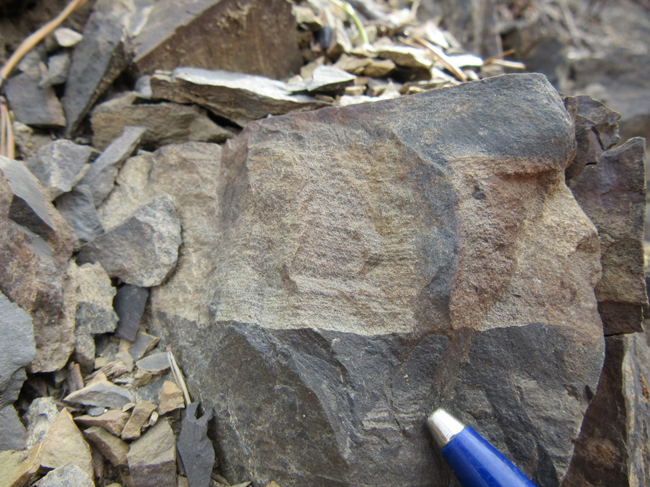

Classic graded bed – sudden, crisp base, and gradually fining away from it…

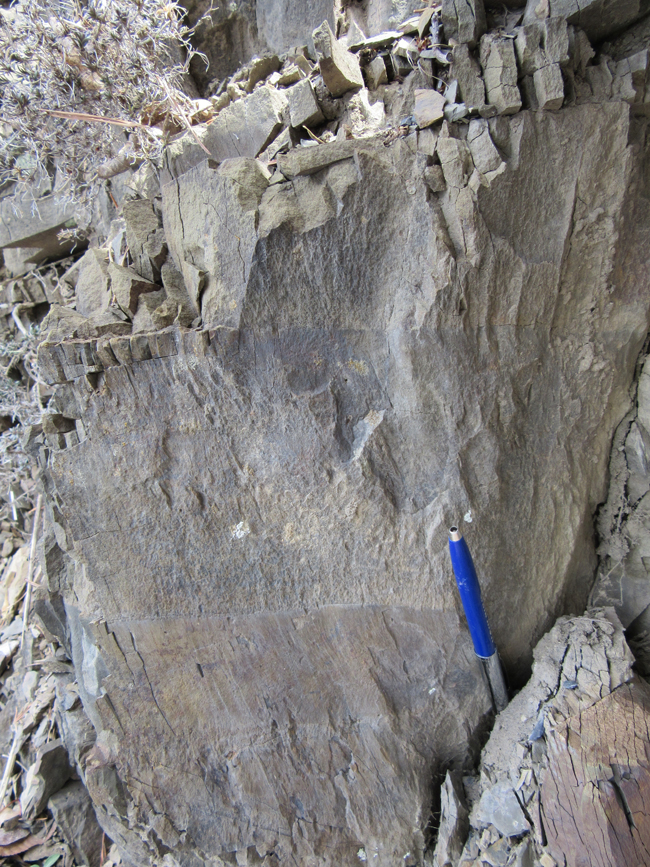

Many such:

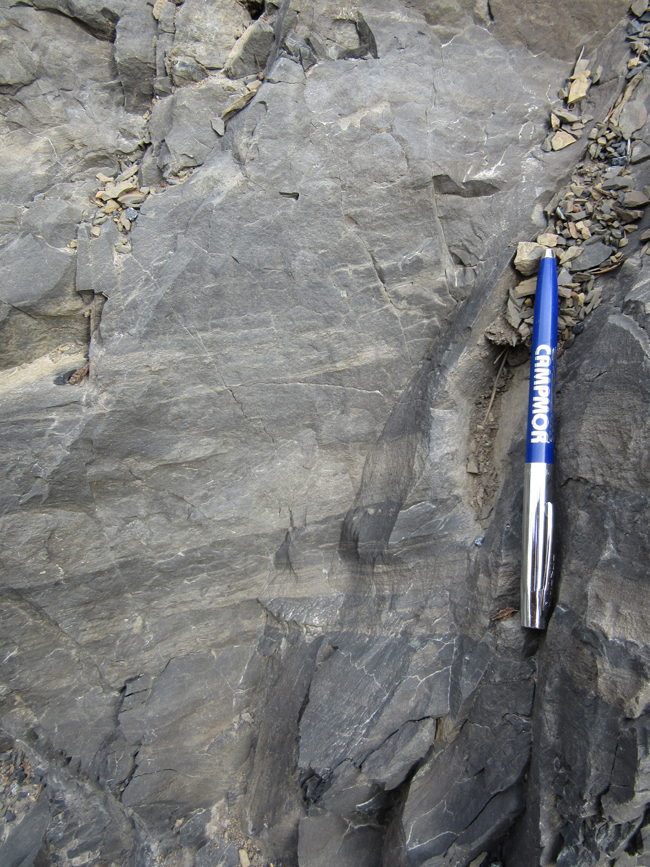

A relatively clean outcrop showing pervasive planar-laminated sands:

Bedding exhibits a variety of attitudes in Edinburg Gap – symptomatic of parasitic folding on the larger Massanutten Synclinorium, no doubt.

Beauties:

Here’s another example, in float, seen to be up-side-down on consideration of its sedimentary structures’ orientations:

Here, the base of a graded bed shows some meager fossil content, mainly preserved as external molds:

Zooming into the right side – crinoid columnals mainly:

Here’s a lone skinny crinoid stem lying elsewhere in the fine sandstone:

Here are some trace fossils – dark mud-filled burrows which cross-cut the lighter-colored sandy turbiditic layers:

Example #2 of trace fossils transecting graded beds:

Example #3:

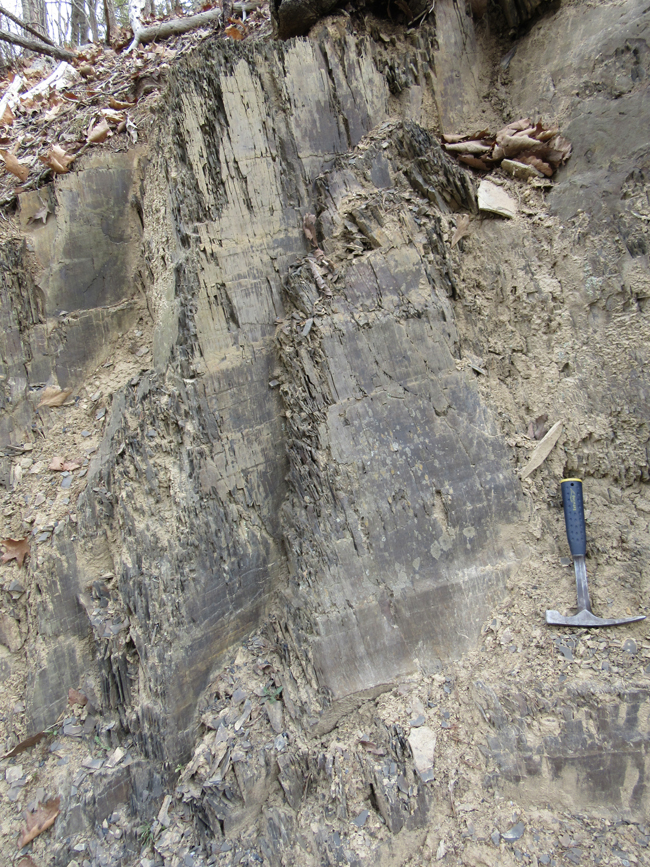

Of course, there isn’t merely a sedimentary / biological story recorded here; structural geology plays an important role in our interpretation, too. These turbidites (rocks deposited by turbidity currents) were involved in Appalachian mountain-building. When ancestral Africa collided with ancestral North America in the orogeny that assembled Pangaea, these strata were squeezed. Pressure solution on a microscopic level imparted a cleavage that’s most pronounced in the shalier layers:

The rock breaks along the cleavage more easily than the bedding, resulting in rectangular scree, each a miniature cross-section of the turbidite layers:

I’ve been driving past these outcrops for almost three years now; but things in my life are so busy that I didn’t get a chance to stop until just last week. That’s nuts! Parenthood has really cut into my geology habit. I have a dozen other examples of this – places close to my home that I just can’t seem to find the time to visit for the purposes of geology.

That said, I’ll note that the Martinsburg Formation is my new favorite formation in Virginia. I love the geopetal structures, the evocative abyssal fan imagery, the imagined violence of the ancient mass wasting, the connection to orogenic processes, the fossils (both body and trace), the later Alleghanian structural overprint. It’s a great formation, and I look forward to learning more about it as the years go by…

I agree that the Martinsburg is an interesting unit. Have you ever read McBride (1962) paper on the Martinsburg? I can send your way if you don’t have, it’s very comprehensive and tons of data.

Spotted this and wondered where it was near Edinburgh. But fascinating all the same. Thanks for posting.

It’s in western Virginia. Not Scotland. Note spelling difference – we pronounce it Edin Burg, with a hard G

Those are some great photos. I recall that one thing you could count on – at least in SW Virginia – was lots of great Martinsburg outcrops/roadcuts.