When snail shells are deposited in a bunch of sediment, they serve as tiny architectural elements, with a “roof” that protects their interiors. Any sediment mixed into the shell’s interior will settle out (more or less horizontally), and then there will be empty space (filled with water, probably) above that. As burial proceeds and diagenesis begins, that pore space may be filled with a mineral deposit, such as sparry calcite.

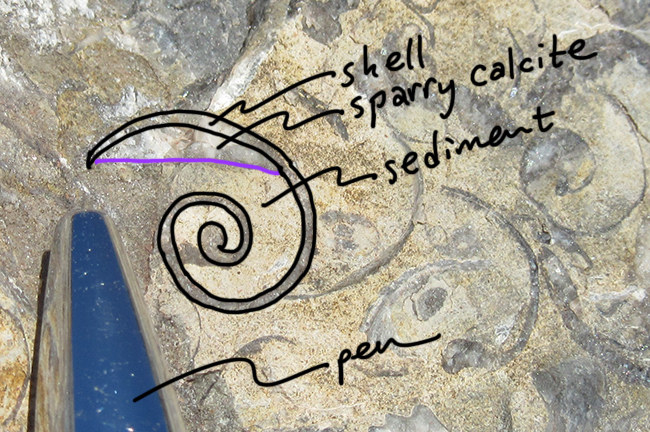

Here is an example from a gastropod rich horizon within the Mississippian-aged Reynolds Limestone member of the Mauch Chunk Formation, exposed on Corridor H, West Virginia:

(There’s another example on the far right of the photo, below the letter “t” in “sediment”.)

The sediment (lime mud) is yellowish gray and granular. The sparry calcite is gray to white and crystalline, continuous with the shell material.

This “cavity fill” structure (where the snail shell is the cavity being filled, partly by entrained mud and partly by diagenetic crystallization) serves as both a paleo-horizontal “level” and a geopetal structure (indicating which way was up when the sediment was deposited).

It’s a cool thing to find – it helps geoscientists orient themselves in outcrop spacetime.

Okay, now try applying the concept to this one: Can you see the same structure?

Scroll down to see if you were right…

(Photo ‘up’ is geopetal ‘up’ in this case, too.)

A macro GigaPan example, from the Permian-aged Hueco Limestone of west Texas:

Link

And another, more subtle, locality unknown:

Link