Because of my commute, I consume multiple books at the same time. I listen to one in the car, and I read another (or more than one other) at home, on traditional paper. This past week, I read Jurassic Park, by Michael Crichton and listened to David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens. I chose the Dickens volume just to have something to listen to that wasn’t NPR coverage of our disastrous modern political era, and I chose Jurassic Park because my son is really into dinosaurs and fossils just now, and I remember it as a great novel. He’s getting an edited version, mind you, cleaned up of the nasty language and violence, as well as descriptions of the men ogling Ellie Satler’s legs. I remember Jurassic Park as being so vibrant and vital a story that (as a high school student and then as an undergraduate) I pressed it on everyone I knew with a scientific frame of mind.

But man, reading it now, in regular comparison with Dickens? Crichton sucks!

Crichton’s novels have always explored the scientific vanguard in the context of various human motives, some noble and some nefarious. They move fast, and are exciting. That holds a reader’s attention, but it’s soooooo different from Dickens, who plots his novels emphasizing character and time, and the beauty that emerges isn’t only in the twists of fate (of which there are several very satisfying ones) but in the details of the characters, in particular their dialogue, which is always distinctive and flavorful. To compare Wilkins Micawber to Uriah Heep to Aunt Betsey Trotwood is to encounter distinctive voices and characters, different essential personalities. In contrast, Crichton’s characters all sound like they speak with the same mouth; there is no nuance or idiosyncrasy. Even the chaos theorist Ian Malcolm, who I think is Crichton’s most distinctive character, is basically a speakerbox for Crichton’s own perspective, and he holds forth in long rants which might as well have been essays or “author’s note”s that Critchton wrote representing himself.

Both novels contain no major characters beyond white people. In Crichton’s book, it’s cringe-inducing to see that all the black characters are introduced as merely “a black man,” though of course none of the white characters are introduced as “a white man.” That they are white is just assumed in the Crichtonverse. The sole exception was geneticist Henry Wu, an Asian-American character. It was a good choice on the part of Steven Spielberg to cast Samuel L. Jackson as John Arnold in the movie version of Jurassic Park, injecting a jot of diversity into what was otherwise a lily-white cast. In another instance, Wu reflects on DNA being an ancient molecule, being present in microbes as well as “human beings, walking around in the streets of the modern world, bouncing their pink new babies.” Not all babies are pink, of course, and this I think reveals Crichton’s blindness to non-white people, his thoughtless racism. Of course, Dickens doesn’t feature any characters from non-European ancestry either, but he was writing in a much less diverse portion of spacetime. I can find it in my heart to excuse Dickens in a way that seems preposterous for a well-educated modern-day American like Crichton. In other words, the context of the novel’s setting and its author’s society are relevant in passing judgement on them. It is also worth noting that the latest film to be adapted from David Copperfield, due out this year, will feature a cast much more diverse than Dickens might have scripted.

Another set of thoughts: rereading Jurassic Park to my son reminded me of how much of my impression of that story had been (re)formed by watching (repeated, I’ll admit) screenings of the film adaptation. Spielberg ended up telling a story that I think was better in several key regards from the novel that inspired it, with (1) the dinosaurs restricted to the island only (the novel has them in mainland Costa Rica both first thing and last thing), and with (2) both Malcolm and Hammond surviving the story to fight another day, and (3) vice versa for Gennaro. Another useful change was (4) swapping the age structure of child characters Lex and Tim, with Lex attaining computer savvy and thus having a positive role to play in the resolution of the plot. In the book, she basically whines the whole time. I liked too how the film had Malcolm as more heroic and less scaredy-cat (5) when he grabbed a flare to distract the T. rex.

A final thought to this little missive: Dickens deserves his reputation for penning excellent literature, and listening to David Copperfield was an absolute delight. It’s an excellent story, and holds up well despite being more than 150 years old.

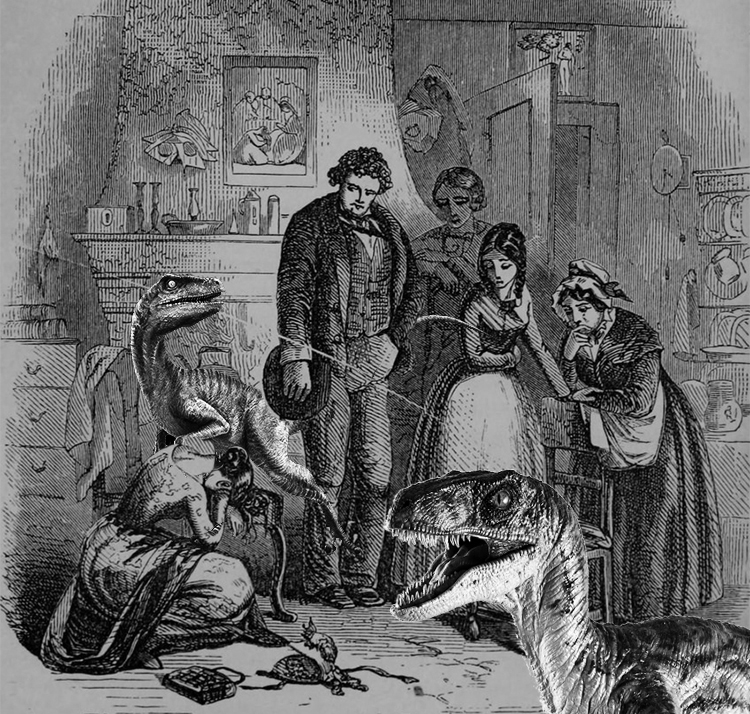

I had thought you were going to talk about Bleak House, the only Dickens novel to feature a non-avian dinosaur…

I’d never heard of it until this moment. Should I read it next?

I read Jurassic Park over a couple of nights when I was in grad school. At the time I was unaware that the movie was being made — but it made sense to me because I thought that it read like a novelization of a movie script.

What did you think of the deviations from book to film in terms of the overall effect?

If you like characters with distinct voices, you might enjoy Wilkie Collins’ novel The Moonstone. Part of the story is told through the letters or written recollections of the various characters, and their voices – and personalities – are quite different to each other. It also has the distinction of being one of the first English-language novels to feature a private/consulting detective, as it precedes Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes by a couple of decades. Plus the titular “moonstone” is a piece of geology!

Cool; I’ll check it out.

Bleak House usually regarded as one of the best two or three Dickens novels. Highly recommended.