I went out last Tuesday to Corridor H, the exemplary new highway cutting through the Valley and Ridge province of eastern West Virginia. Joining me was former student Alan Pitts, a devotee of Corridor H from way back in the early days when we just called it “New Route 55.”

The boondoggle highway is now open all the way west to the Allegheny Front, practically into the Canaan Valley. On Tuesday, we went all the way to physiographic boundary, right near the big line of windmills that marks the transition from the Appalachian Plateaus to the first valley of the Valley & Ridge. This is the first of several posts of the new stuff we saw on that field trip.

The steam plume you see in the photo below is the coal-fired power plant at Mount Storm. Note the red beds (Hampshire Formation, presumably) and the snow cover:

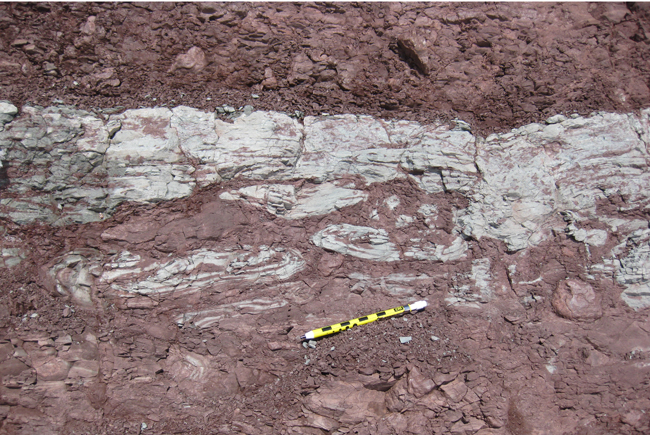

The westernmost outcrop we examined in detail is this one, which we inferred to be the Hampshire Formation (Devonian red beds / molasse), a 2000-foot-thick stack of fluvial and floodplain sediments deposited on a massive delta complex that extended westward into the Kaskaskia epeiric sea from the Acadian Orogen. You can see that the exposure is pretty great on these Corridor H roadcuts, but that we had a moderate amount of snow and ice to cope with that day…

We saw some interesting “jellyroll” looking structures there… potential features indicating the “rolling up” of sedimentary layers as they destabilized, slumped and tumbled downslope.

Unfortunately, these “jellyrolls” were only delineated by the alternation between oxidized (red) and reduced (gray-green) layering. I would have preferred some more robust criterion, such as grain size differences. Redox reaction fronts can be an indication of primary sedimentary layering, but they can also be diagenetic, or controlled by structures like joints. Just the same, these ones are pretty cool, even if I’m not 100% positive that they represent soft-sediment deformation.

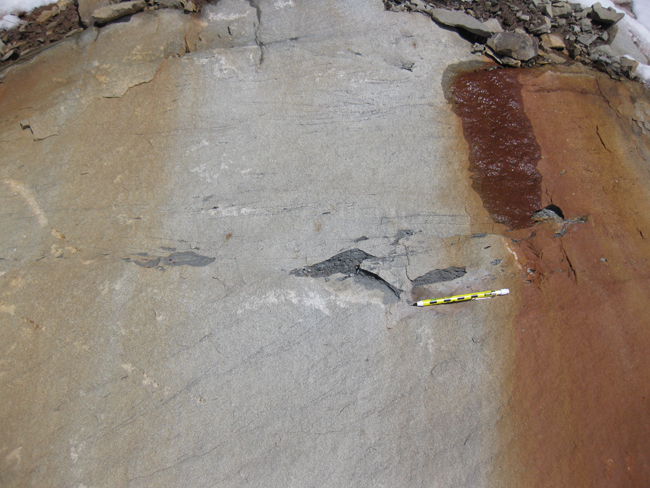

There was a thick sandstone unit there, too. Can you spot the cross-bedding in this exposure?

Here’s some more cross-bedding. Note the truncated tops to the cross-beds (indicating these beds are oriented with “up” being stratigraphic “up”; that is to say: they have not been tectonically inverted). Also, note the gray mud rip-up clasts right at the boundary between one massive sandstone bed and the next one overlying it:

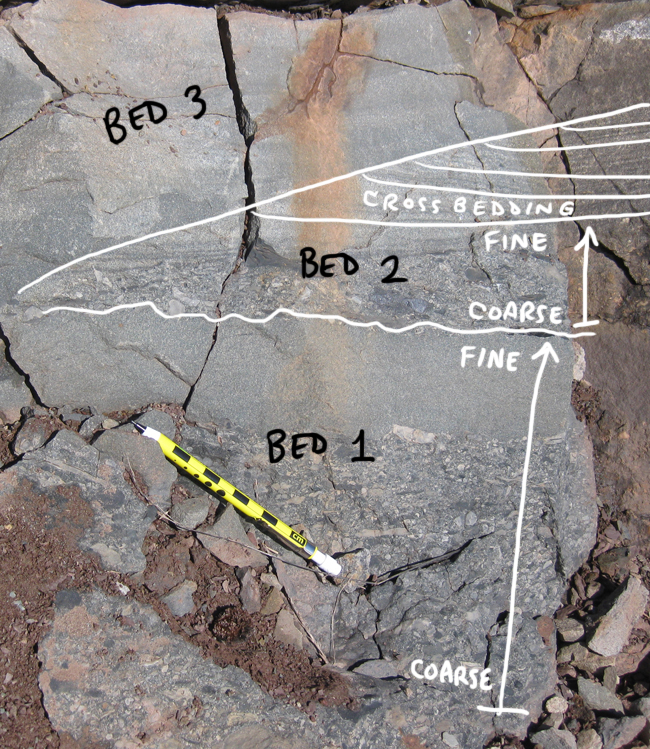

Here’s a slightly more complicated scene: What do you see?

Surely you noted the coarsening of the grain size. Part of this outcrop is conglomerate: a sedimentary rock made of pebbles. Here’s what I see:

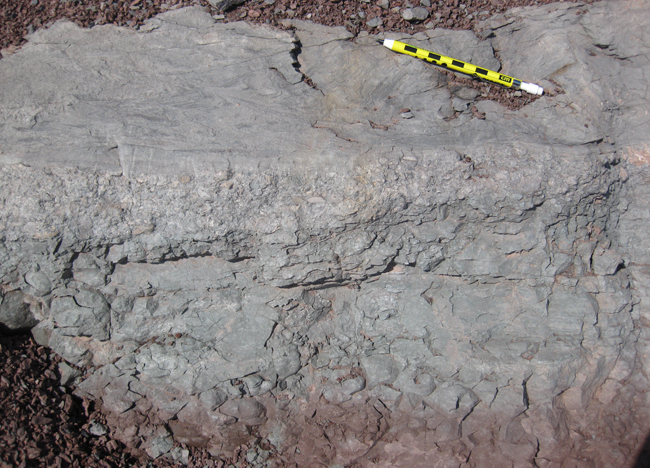

And here’s another conglomeratic bed, full of small carbonate rip-up clasts. Where did the carbonate come from? This is surprising to me: the Hampshire Formation is supposed to be terrestrial. Are these limestone clasts derived from the Acadian Highlands themselves? Or is this contemporaneous carbonate from an adjacent depositional environment?

You noted the white weathering rind on the big one at the bottom of that last picture, right?

Here’s a look at another outcrop, further down the road. More red beds. Note the rhythmic alternation between siltstone and shale:

Note how they both get thinner as you work your way up in the sequence.

There are reduced layers in here, too.

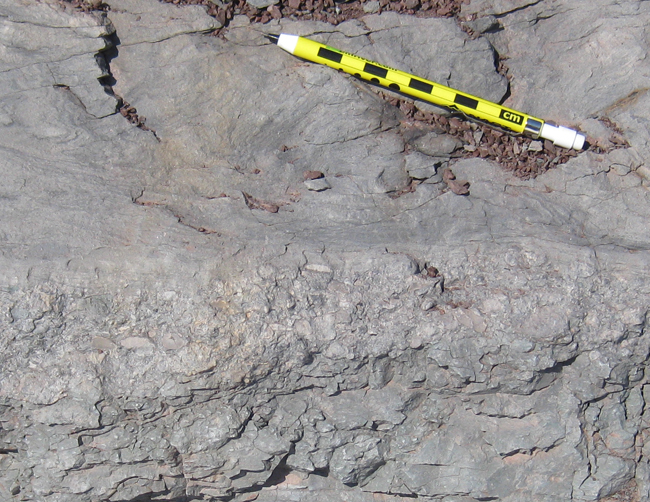

Note the coarse grain size in the middle of this gray-green reduced stratum:

If you trace this layer out to the right, you will find that it abruptly truncates, in contact with the fine-grained red beds:

My interpretation:

Note the cross-cutting relationship here: the gray-green conglomerate must be younger than the red siltstone and shale, since it cuts across them.

A last look at this outcrop as we prepare to leave:

Note the low-angle cross-beds in the lower red bed unit (bounded above and below by thin greenish reduced layers).

Our third stop on the Allegheny Front was this roadcut… Click through for a full sized panorama of the outcrop.

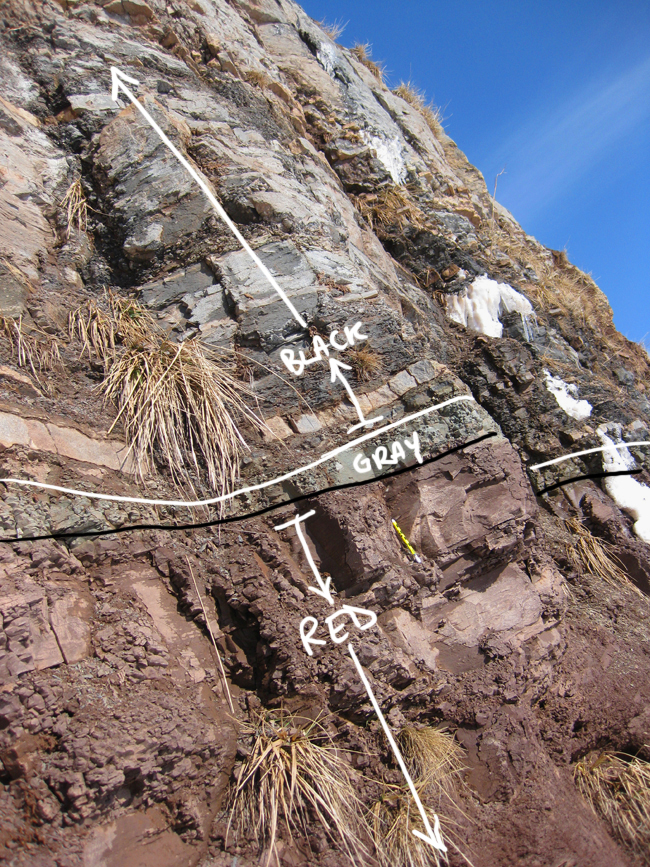

This caught our eye because that’s not a whitish sandstone layer sandwiched between red beds. Instead, it’s a black siltstone / shale unit.

The black layer, about 5 m thick, was a limestone / limy siltstone / shale, with alternating beds 2-5 cm thick. It gets more massive toward the top:

In it, we found marine fossils, like these articulate brachiopods…

… and these gastropods (snails):

Wow – this surprised us. Neither of us thought the Hampshire Formation had any marine strata within it. Was this black, limy, fossiliferous layer representative of a small transgression (sea level rise) over our deltaic floodplains (red beds)? Here’s a closer look at the base of the black unit:

It seems to have come on pretty suddenly. That gray zone could reflect primary coloration, or its coloring could be a secondary diagenetic reaction between the oxidized zone below and the carbon-rich limestone above.

So, in summary: We interpret the black layer as resulting from low-oxygen marine deposition. But that doesn’t sound like the Hampshire Formation. Two possibilities occur to me: Does this suddenly black limy interval indicate that this isn’t the Hampshire Formation? Or did we just ‘discover’ a new marine portion of a previously-thought-to-be-terrestrial-only geologic unit?

Any thoughts?

Well, here’s a reference to fossil evidence of a thin brakish/estuarine environment in Hampshire beds in WV; not quite like the nice brachs and gastros you’ve got there: http://www.pages.geo.wvu.edu/~kammer/reprints/Feldmannetal1986.pdf. It would be interesting to see where your outcrop is stratigraphically. Regardless, that is some neat stuff from a great roadcut, Beautiful.

Those brachs look like productids–any way these rocks could be Carboniferous (Mississippian)? I’ve had the devil of a time trying to find a decent online stratigraphic chart for West Virginia, but I found suggestions in the legend of one online map that there are Mississippian rocks with redbeds and limestone in the general area that would be younger than your Hampshire Formation. Maybe I’m out to lunch.

Yes, they certainly could be – as that’s what makes up the uppermost layers exposed on the Appalachian Plateaus. This is just below the rim of the plateau, maybe 100 or 200 feet, and certainly “within reach” of strata of those ages. Can you point me to the map you found? I was frustrated while preparing this post that I couldn’t zoom in on a digital geologic map of the area.

Callan, it was this map:

http://www.wvgs.wvnet.edu/www/maps/geomap.htm

Pretty lame, I agree, but it was about all I could find in a few minutes of searching, without turning this into a research project. Anyway, it’s got nothing more detailed than the legend colour chips that say “…Mississippian…Limestone, red beds, shale, and sandstone”. The colour chip for Devonian says “…Red beds, shale, sandstone, limestone, and chert”. Pretty much identical descriptions, which is the only reason I mused that Mississippian rocks could masquerade as Devonian (i.e. Hampshire Fm.) in this general area.

The brachs in your photo are–superficially–dead ringers for productids we have in the upper Banff Formation (Mississippian: Tournaisian) here in Alberta. A knee-jerk reaction on my part, and a pretty tenuous basis for speculation (productids range from Lower Devonian to Penn. or Perm. IIRC). And beyond that, I’m WAY outside my comfort zone discussing geology of the eastern US, so I’ll let you guys figure it out! I’ll be watching with interest.

Maybe a Reynolds Lst (Blufield) or Little Stone Gap (Hinton) equivalent.

If you were near Scherr, WV; you were in the area where this WVU MS thesis was done – on the Reynolds Limestone Mbr. of the Bluefield Formation (Chesterian/Numerian, Upper Mississippian): http://wvuscholar.wvu.edu:8881//exlibris/dtl/d3_1/apache_media/L2V4bGlicmlzL2R0bC9kM18xL2FwYWNoZV9tZWRpYS83NDM2.pdf

Chances are the Little Stone Gap Limestone member of the Hinton Formation is exposed near there, too.

Personally, to me, it looks a lot like Hinton strata (like you might see on 460 between Bluefield WV and Pearisburg VA

Ugh… Namurian not “Numerian.” Yeesh, so much for memory.

Also, I agree with Howard – the brach in the 2nd fossil photo looks like a productid.

The young earthers over at the institute for creationist research have already snatched your article up as “evidence” of a global flood! Complete with quoting your article out of context. http://www.icr.org/article/8014/ A little scientific inquiry goes a long way. But arguing with idiots is always a pointless endeavor.