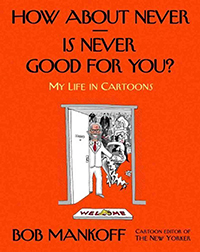

My friend Joe Cancellare knows that I like cartoons, and that I even draw a few cartoons myself. He surprised me a couple weeks ago with a gift of a book – a new memoir by New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff. This was a real treat – it explores (a) the idea of how cartoons work (or don’t), (b) Mankoff’s own journey as a cartoonist, entrepreneur, and eventual editor, and (c) the inside story of how The New Yorker magazine manages its cartoons and cartoonists. The unwieldy title of the book is the caption from one of Mankoff’s most popular cartoons, and while I don’t love that (I mean, look how long the title of this blog post is!), I’m glad to have read the book.

My friend Joe Cancellare knows that I like cartoons, and that I even draw a few cartoons myself. He surprised me a couple weeks ago with a gift of a book – a new memoir by New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff. This was a real treat – it explores (a) the idea of how cartoons work (or don’t), (b) Mankoff’s own journey as a cartoonist, entrepreneur, and eventual editor, and (c) the inside story of how The New Yorker magazine manages its cartoons and cartoonists. The unwieldy title of the book is the caption from one of Mankoff’s most popular cartoons, and while I don’t love that (I mean, look how long the title of this blog post is!), I’m glad to have read the book.

I’ve been a reader of The New Yorker for about a decade now, and I’m always interested in the cartoons, which are a diverse lot, some brilliant and incisive, others bizarre and head-spinning. I came to the magazine via the route of John McPhee, who has written some of the most lucid and evocative essays (and books) about geology ever written. Once I dipped into its pages, I found extraordinarily well-written profiles, criticism, and essays, as well as intelligent indulgences and about 40% stuff I didn’t care about. But the remaining 60% was good, really good.

Anyhow, each cartoon is a stand-alone (usually 1-panel) drawing, with (most of the time) a caption beneath it. The cartoonists who draw these images, who dream up the humorous situations, are a mix of regulars and “fresh blood.” The regulars get to you after a while – their drawing styles and their distinctive thought processes get to feel like old friends. Sampling their little boluses of humor is a great part of my weekly routine.

If you’re not into cartoons, or if you’re not into The New Yorker, there’s no way you’re going to like this book, but if you know what I’m talking about, then it is probably worth your time to read.

I miss Drumlin, and his human.