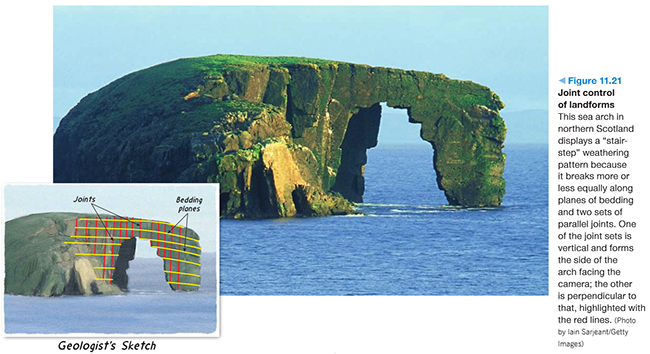

A distinctive landform in Shetland can be found offshore of Eshaness, a blocky sea arch islet called Dore Holm (“Door Island”):

That’s a lovely beast, you must admit. I made sure to feature a photo of it in my article about the geology of Shetland for EARTH magazine. You should read that, if you haven’t already.

I was delighted to view Dore Holm for myself last summer because the previous spring I had selected it as an example to use when discussing joints in the newly-revised 13th edition of Essentials of Geology by Lutgens, Tarbuck, and Tasa. I helped revise the chapter on Structural Geology and Mountain-Building (Ch. 11), and suggested Dore Holm as an aesthetically-elegant example of jointing. Here’s the figure from the book:

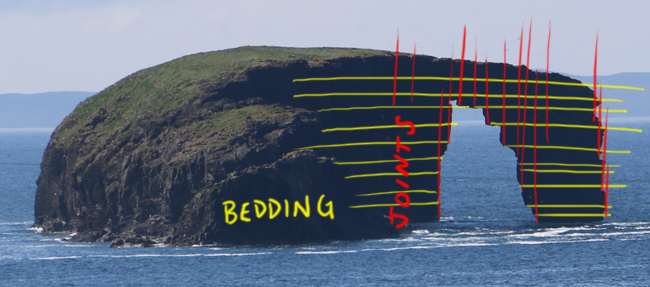

I’m pleased that my suggestions on the color coding of the annotations was followed, but here’s my version of the scene, using my own photo:

A few quick comments on the #dataviz aspects of this image: I like color coding labels to match the thing they are describing. I also really don’t like using arrows for labels. I prefer to retain arrows exclusively for indicating motion. The authors of the book made some different decisions than I did, and that’s their prerogative, but I like mine better.

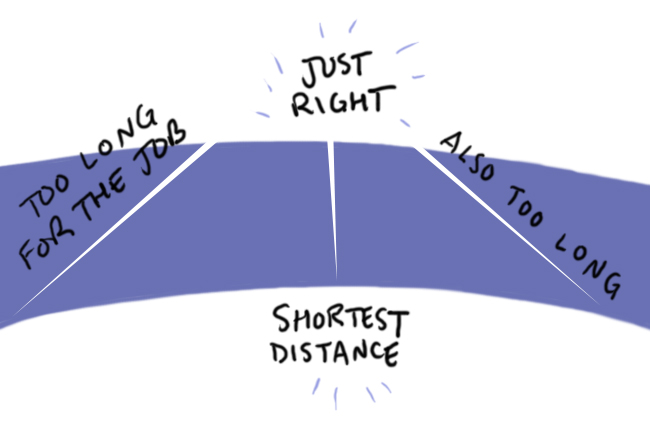

So what about the geology of this situation? When relatively stiff sedimentary or volcanic beds (volcanic, in this case: Devonian in age) are stressed in the brittle regime (i.e. either cold and low confining pressure, or rapidly), they break. The breaking is accomplished with fractures that show little to no displacement, called joints. It takes energy to break a rock, and so the easiest way to break it is to make the shortest joint possible. For a stiff tabular bed, that means breaking it perpendicular to the plane of the bedding. These orthogonal joint sets are among the most common structures to be observed in stratified rocks. Let’s look at one of these beds from the side, and imagine three hypothetical crack orientations relative to the bed:

The one that’s oriented perpendicular to the bed has the shortest distance to travel, the least amount of rock to transect, the least number of bonds to break. It is thus the most energetically efficient orientation, the easiest job to accomplish.

Clever eyes among you will have noticed that there’s another joint set in the photo of Dore Holm, but it’s parallel to the plane of the 2D image (perpendicular to the line of the photographer’s perspective). If you take a view looking down on the site, say from Google Earth, you are looking down on the more-or-less horizontal volcanic bedding plane. You can immediately see that there’s another, mutually orthogonal joint set sculpting the island:

This second joint set is perpendicular to the first, and also perpendicular to bedding. These joints intersect in X or T patterns (I can’t tell which from here, but I’d venture to guess X), different from the Y-shaped intersections detailed yesterday.

The three mutually-perpendicular fracture sets or planes of weakness divide the rock up into a Qbert style pile of blocks that the ocean can then pick away at in order to sculpt the island. When the erosive power of wave action works in tandem with the geometry of systematically-broken rock, we get neat features like Dore Holm. It’s a scenic place, but it also offers an exemplary lesson in the deformation and weathering of rocks on our planet’s surface. The island’s shape is a reflection of the parsimonious nature of the expenditure of energy in natural deformation.