Today’s Friday fold takes me back 25 years, to when I visited the Outdoor Lab with my science class in Arlington County Public Schools. I revisited this exemplary outdoor education facility on Tuesday, at the invitation of its director, Neil Heinekamp.

Neil wanted a geology “expert” to take a look at their rocks, and I wanted a chance to check out their rocks as part of my expanding examination of the geologic story of Thoroughfare Gap. Win-win, as they say.

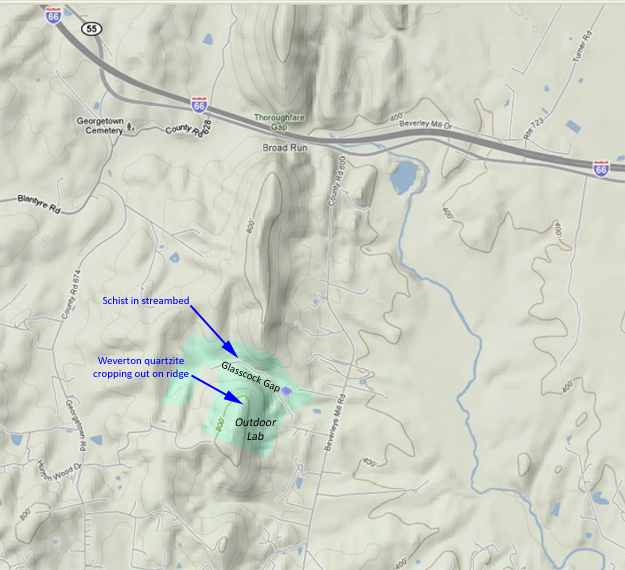

Here’s a map for some context: the Outdoor Lab is along strike from Thoroughfare Gap, to the south along the ridge of the Bull Run Mountains. It even has its own water gap, called Glasscock Gap, a central valley on which the Outdoor Lab property is situated:

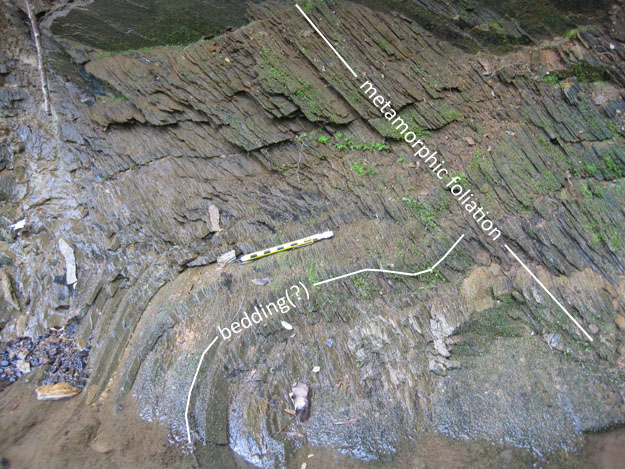

The first spot Neil took me was the stream that cut Glasscock Gap. Exposed there are saprolitic (rotten) schists, presumably of the Cambrian Harpers Formation, but potentially just a muddy facies in the Weverton Formation. The first thing to jump out at my eyes was this:

…which I interpret thusly:

Foliation was prominent; the defining feature of this outcrop. The mechanical/compositional layering that I’m interpreting as bedding was only seen in a couple of places. I pointed this out to Neil and his staffers, Anthony and Jess.

Establishing the relative timing of the geologic events was important to them, so this outcrop was useful: Deposition first, metamorphism second. They also wanted me to settle a perpetual question among their student clients: is vein quartz an igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic rock? The kids really want to shoehorn milky quartz into one of those three families. I suggested the best way I could think of to explain it was that milky quartz veins are a feature associated with metamorphic rocks, but don’t really qualify as rock units of their own.

After this digression, we noticed that right next to the bedding/cleavage display was a small high-angle fault zone, though we couldn’t detect the kinematics of offset, the rock was pulverized, altered, and more susceptible to weathering along than the schist next door:

Next, we hiked up the mountain, encountering a little bit of Catoctin greenstone float along the way, to see the quartzite outcrop on top. I set Neil and his two staffers out to search for cross-bedding, and we found a couple of candidates, but nothing that I would want to hang my hat on. On the other hand, we did find some nice asymmetric folds upsetting the thin dark layers (bedding?), such as this set (view is to the north, so west is left and east is right):

They’re pretty subtle, so it’s okay if they don’t jump out at you. Here, let me highlight them, and then you can go back and look in the original, unadorned image:

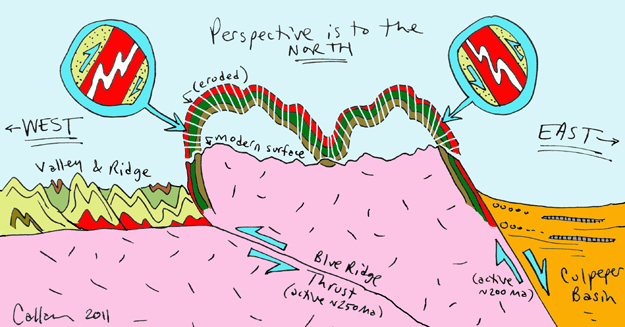

The asymmetry of the limb length in these folds indicates that the top/right is moving up and to the left relative to the bottom/left. In other words, east is moving up and over west. This is symptomatic of the overall kinematics of the Blue Ridge province, which is interpreted to have been in an original position lower in the crust and further to the east. During the Alleghanian collision with Africa, it snapped off (thick skinned tectonics, arched upwards, and slid up and over much younger rocks (the contorted sedimentary strata of the Valley & Ridge province). It became folded into the Blue Ridge Anticlinorium. So these small-scale parasitic “S” folds are following Pumpelly’s Rule in telling us in miniature the regional-scale story of the Blue Ridge.

Let me sketch it out for you, showing the Blue Ridge province in the context of the Valley & Ridge province to the west, and the younger Culpeper Basin Triassic rift valley to the east:

(Click through this image for a bigger version.) As we look down the axis of the Appalachian mountain belt towards the north-northeast, we would expect to see “Z” folds on the west limb of the Blue Ridge anticlinorium, and “S” folds on the east (like at the Outdoor Lab). The opposite “sense of offset” would be expected if we looked south along strike of the mountain range.

This too, is visible at the Outdoor Lab. We walked to the other end of the outcrop, swiveled 180°, and looked back. We were now looking south. Here’s a photo to show you what we saw. East is now on the left; west is on the right. You’ll see similar asymmetric folds, but in the opposite orientation (top to the right), which still translates as “east over west.”

Annotated and highlighted, that would look something like this:

These small-scale folds, revealing the regional tectonic story of the Blue Ridge province, will serve as this week’s Friday fold, I reckon.

…And that’s about it* for the new and exciting geology we witnessed at the Outdoor Lab on Tuesday. Thanks to Neil, Anthony, and Jess for hosting me!

*I’m not counting the peewees, box turtles, toads, mushrooms, snapping turtle, salamander eggs, ladyslippers, Louisiana waterthrush nest, wild turkey nest, mountain laurel, oaks, ants, or spiders that we saw.

0 thoughts on “Friday fold(s): the Outdoor Lab”