![]() Yesterday I attended a climate change briefing hosted by the American Meteorological Society (in conjunction with NSF, AGU, AAAS, and the American Statistical Association). It was in the Hart Senate Office Building, but I didn’t see any senators at the briefing.

Yesterday I attended a climate change briefing hosted by the American Meteorological Society (in conjunction with NSF, AGU, AAAS, and the American Statistical Association). It was in the Hart Senate Office Building, but I didn’t see any senators at the briefing.

It was an interesting format: 3 talented speakers giving 3 “fifteen-minute” presentations (really more like 25 minutes apiece), each focusing on a different aspect of climate change: Mike Oppenheimer (Princeton) spoke about the science, Jon Krosnick (Stanford) spoke about public perception, and Norm Ornstein (American Enterprise Institute) spoke about the current political landscape.

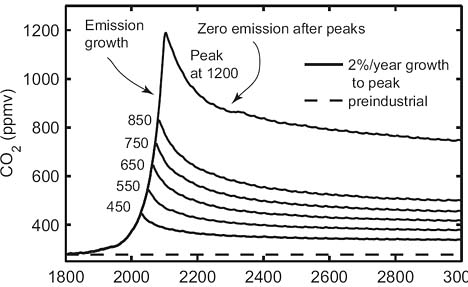

Oppenheimer gave some of the basics about the greenhouse effect, etc., then showed the striking graph from Solomon, et al. (2009):

This is a sobering chart: the ~100 ppm increase in CO2 in the past century has a radiative forcing of about ~1.5 Watts/m2, and that’s yielded a bit less that 1°C of global warming. But when you project emissions into the future, you see that the CO2 we’ve emitted has a really long residence time in the atmosphere. If emissions were to stop completely at different points in the next century, we would see peak emissions of 450, 550, 650, 750, 850, or 1200 ppm, after which the numbers would slowly decline, but then ~stabilize at levels well above the preindustrial background level of 285 ppm. In other words, we’re locked in to irreversible climate change to some extent; it’s only a question of degree (pun intended). With reinforcing feedbacks, the resulting temperature changes could be severe.

Oppenheimer then moved on to discuss ice melting. He talked about the precipitous 2007 decline in Arctic sea ice, and pointed out that in 2008 and 2009 the ice there had rebounded to the (negative) trend line. “This means it wasn’t terrible,” he said. “It was just really bad.”

Next, he used a good visualization to talk about potential melting in the future. He showed maps of Greenland and Antarctica, with the relevant ice masses overprinted with their potential contribution to sea level rise. He soberly reminded the audience that while melting of Greenland and West Antarctica were immediate concerns, East Antarctica was “likely not going anywhere soon.”

Jon Krosnick was next to speak. He is interested in the intersection of communication, psychology, and politics, and conducts a lot of survey research. He pointed out that there has been a lot of talk in the mainstream media lately about pronounced declines in public acceptance of climate change science. For instance, a Pew poll found a decrease from 71% to 57% of the public who accept anthropogenic climate change. In a critique of the questions pollsters used to arrive at that conclusion, Krosnick found significant methodological flaws, and showed how his team have countered those pitfalls with better question wording. Tenses were mixed up, questions asked only about the “last few decades,” questions were not about responders’ opinions but about what they “had read and heard,” or the questions were laughably complex, “which increases the cognitive burden for the responder,” Krosnick said. He also pointed out that the Pew survey compared a summer poll with a winter poll, and suggested that the time of year you ask people questions about global warming influences how they respond.

So his research group used better questions, and came up with a shift from 80% to 75% over the same time period. Yes, that’s a decline. Yes, that’s statistically significant. But it’s also 75% of those surveyed. Krosnick reminded the audience that 3/4 is a big number, a huge number of people who think anthropogenic climate change is real. There is not a huge decline, and “believers” are in a solid majority.

Still, what’s behind the decline? Krosnick postulated five potential explanations: (1) Trust in science was declining, (2) the economic situtation has made people reluct to shoulder the burden of dealing with climate change, (3) Republican political leaders (he didn’t say “Inhofe,” but that’s surely who he was referring to) are making headway with the public, (4) “skeptical” scientists are making headway with the public, or (5) 2008 broke the warming trend and had the lowest temperatures in the most recent decade. He then evaluated each of these using his survey research methods.

He found no significant change in the trust in scientists. It remains at ~70%. So much for explanation #1. He actually found a (small) increase in the willingness to pay for remedial policies, in spite of the bad economy, so #2 is out, too. In addressing the influence of the Inhofes, he found no real chance among Republicans as compared to Democrats (presumably Republicans would be more willing to be influenced by Inhofe’s statements). He also ruled out the skeptical scientists’ influence, as people who have a low trust in scientists have both a correct perception of scientific consensus and a correct perception of the overall temperature change. And that left #5, the 2008 break in temperature trends. He suggested that when it warms up again, they will shift back. As with a year’s cooler weather, the cooler perception is a temporary aberration which will vanish as soon as people “stick their finger out the window” and find it to be hot again.

The final speaker was Norm Ornstein. I was very impressed by Ornstein’s diction and mastery of the Washington political landscape. He’s a very smart guy, who assumed the podium and stuck his hands in his pockets and (sans PowerPoint) spoke extemporaneously and in great detail about why politicians do what they do. I was impressed with his erudition and competent demeanor. He noted that there is a deep dysfunction in the American political system, and that this dysfunction is systematic: that is, it doesn’t change with the election of new officials. In 40 years of observing Washington politics from the inside, Ornstein said that this is the most dysfunctional he has ever seen it. He said that it’s really unlikely to get meaningful climate legislation passed unless the health care bill passes first. Obama needs a record of success in order to push his other agenda items forward, and the obstinacy of the Republican caucus has made his first year ineffective, which puts Democratic Congresspeople in a tricky spot “going out on a limb” to support him in his second year (as they are up for re-election then).

I tend to think about policy rather than politics, so this “reality check” about how Congresspeople think was insightful to me. In spite of strong science (Oppenheimer) and strong public sentiment (Krosnick), the reality of the political landscape suggests we’re not going to see meaningful climate legislation any time soon.

And with that, I went to Union Station and got some lunch.

_________________________________________________

Solomon, S., Plattner, G., Knutti, R., & Friedlingstein, P. (2009). Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106 (6), 1704-1709 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0812721106

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (Oct. 11, 2009) Fewer Americans See Solid Evidence of Global Warming. Washington, DC.

thanks for this great summary, appreciate you writing it

Second Brian, nice piece; thanks!

David Archer’s The Long Thaw is a good summary of the problem of the looonnnnggggg time requirement for the long-term carbon fluxes to take excess C out of the short-term system. A more technical version is his co-authored paper in AREPS: Atmospheric Lifetime of Fossil Fuel Carbon Dioxide

David Archer, Michael Eby, Victor Brovkin, Andy Ridgwell, Long Cao, Uwe Mikolajewicz, Ken Caldeira, Katsumi Matsumoto, Guy Munhoven, Alvaro Montenegro, Kathy Tokos

Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2009 37, 117-134